THE GRAND STORY OF THE BRITISH DELHI DURBARS: SPECTACLE AND SOVEREIGNTY

- Related toModern History, Polity

- Published on6 June 2025

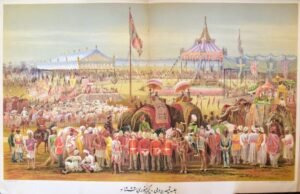

Imagine a spectacle so grand it could dwarf the opening ceremony of the Olympics. Picture a temporary city of elaborate tents, bustling with maharajas adorned in priceless jewels, soldiers in immaculate uniforms, and the highest echelons of a global empire. Now, place this scene in the heart of India, under the banner of the British Raj. This wasn’t a fantasy; this was the Delhi Durbar. But what was the point of such breathtaking extravagance? Was it merely a celebration, or was it something more? The story of the three great Delhi Durbars is a captivating tale of political theatre, imperial ambition, and Indian pageantry, where every jewel and every salute carried the weight of history. It’s a story that reveals not just the might of the British Empire, but also the subtle currents of resistance that would eventually lead to its decline.

Imagine a spectacle so grand it could dwarf the opening ceremony of the Olympics. Picture a temporary city of elaborate tents, bustling with maharajas adorned in priceless jewels, soldiers in immaculate uniforms, and the highest echelons of a global empire. Now, place this scene in the heart of India, under the banner of the British Raj. This wasn’t a fantasy; this was the Delhi Durbar. But what was the point of such breathtaking extravagance? Was it merely a celebration, or was it something more? The story of the three great Delhi Durbars is a captivating tale of political theatre, imperial ambition, and Indian pageantry, where every jewel and every salute carried the weight of history. It’s a story that reveals not just the might of the British Empire, but also the subtle currents of resistance that would eventually lead to its decline.

What Exactly Was a ‘Durbar’?

Before we step into these grand assemblies, it’s worth understanding the term itself. ‘Durbar’ is a Persian word, deeply ingrained in Indian political life for centuries. It refers to a royal court or a formal gathering where a ruler would conduct state business, receive dignitaries, and connect with his subjects. The Mughal Emperors were masters of the Durbar, using it as a stage to project their power, justice, and magnificence.

When the British solidified their control over India, they recognized the power of this tradition. In a classic move of imperial statecraft, they co-opted the concept. They didn’t just want to rule India; they wanted to be seen as the legitimate successors to its imperial legacy. The British Delhi Durbar was their meticulously crafted version of this ancient practice—an imperial spectacle designed to awe, to legitimize, and to bind the Indian princely states to the British Crown.

The First Act: The 1877 ‘Proclamation Durbar’

The first of these grand events, held on January 1, 1877, was less a popular festival and more a solemn, official affair. Its purpose was singular and strategic: to formally proclaim Queen Victoria as the Empress of India. This was a significant political move. Occurring less than two decades after the tumultuous Revolt of 1857, the Durbar was intended to cement the direct rule of the British Crown over India, replacing the East India Company. It was a message of permanence and power.

Lord Lytton, the Viceroy of India, presided over the ceremony. Maharajas, Nawabs, and intellectuals from across the subcontinent were summoned to Coronation Park in Delhi to witness the event and pay homage. Medals were struck, titles were conferred, and a message from the Queen herself was read out, promising liberty, equity, and justice.

However, this glittering display of power was set against a deeply tragic backdrop. At the very same time, large parts of India were in the grip of the Great Famine of 1876-78, which would claim millions of lives. The decision to spend vast sums on the Durbar while so many suffered was seen by many as a profound display of imperial indifference. This stark contrast was not lost on the emerging Indian consciousness.

Amidst the pageantry, a quiet but powerful moment of dissent occurred. Ganesh Vasudeo Joshi, a social reformer representing the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, rose to speak. Dressed in hand-spun khadi—a potent symbol of self-reliance—he politely but firmly put forth a revolutionary demand: that Indians be granted the same political and social status as British subjects. In the heart of an event designed to celebrate imperial subjugation, the first formal call for Indian self-rule was made. The seeds of the independence movement were being sown.

The Zenith of Pageantry: The 1903 Curzon Durbar

If the 1877 Durbar was a formal statement, the 1903 Durbar was an explosion of imperial triumphalism. Held to celebrate the succession of King Edward VII, this event was the magnum opus of Lord Curzon, a Viceroy known for his administrative zeal and his unparalleled love for pomp and ceremony. Curzon aimed to create a spectacle so dazzling it would be etched in memory forever, and by all accounts, he succeeded.

For a few months, a deserted plain outside Delhi was transformed into a magnificent tented city. It had its own temporary railway, a post office issuing special stamps, telephone lines, hospitals, and a police force. Souvenir guidebooks were sold, and marketing opportunities were cleverly exploited. This was not just a ceremony; it was an immaculately planned mega-event.

Although King Edward VII did not attend himself, sending his brother instead, the grandeur was undiminished. The festivities began with Lord and Lady Curzon making a grand entry on elephants, some of whose tusks were adorned with massive gold candelabras. They were followed by a procession of Indian princes, each showcasing the most spectacular jewels from their centuries-old collections. It was, perhaps, the greatest concentration of wealth and gems ever seen in one place.

The Durbar featured days of polo matches, grand balls, and massive military reviews led by Lord Kitchener, the Commander-in-Chief. In a fascinating blend of tradition and modernity, the event was extensively captured on film. These movie clips, shown in makeshift cinemas across India, were immensely popular and are often credited with launching the country’s early film industry. The spectacle was no longer just for the attendees; its message of imperial might was now being broadcast to the masses. The highlight for the elite was the grand coronation ball, where Lady Curzon famously wore her spectacular peacock gown, a dress embroidered with gold and silver thread and studded with beetle-wing iridescence.

The Royal Arrival: The 1911 Durbar

The Delhi Durbar of 1911 was unique for one monumental reason: it was the only one attended by a reigning British sovereign. King George V and Queen Mary traveled to India to be proclaimed Emperor and Empress. This was the empire at its most personal, bringing the monarch face-to-face with his Indian subjects.

The Delhi Durbar of 1911 was unique for one monumental reason: it was the only one attended by a reigning British sovereign. King George V and Queen Mary traveled to India to be proclaimed Emperor and Empress. This was the empire at its most personal, bringing the monarch face-to-face with his Indian subjects.

The royal couple’s arrival in Delhi was a spectacle in itself, with a State Entry involving 50,000 troops. The Durbar ceremony, held on December 12, was a meticulously organized affair. The King-Emperor wore the newly created Imperial Crown of India, a breathtaking crown laden with over 6,000 diamonds, sapphires, emeralds, and rubies.

This Durbar was not just about ceremony; it was the occasion for two major political announcements. First, the King-Emperor declared that the capital of British India would be moved from Calcutta to Delhi. This was a hugely symbolic gesture. Delhi was the historic seat of power for many Indian empires, including the Mughals, and by moving the capital, the British were once again asserting themselves as their rightful successors. Second, the deeply unpopular 1905 Partition of Bengal was annulled, a concession to the growing nationalist sentiment that had fueled widespread protests.

However, this Durbar is also remembered for a moment of quiet defiance that created a storm of controversy. When Maharaja Sayajirao III, the Gaekwar of Baroda, approached the royal thrones to pay homage, he did so without his finest jewels, gave a simple bow instead of the expected deep obeisance, and then turned his back on the royals as he walked away. This gesture, whether intentional or not, was widely interpreted as a sign of dissent against British rule, sending shockwaves through the imperial establishment.

Following the main event, the King and Queen also made an appearance at the Red Fort’s Jharokha—the royal balcony—for a public darshan, another tradition borrowed directly from the Mughals, to greet the hundreds of thousands of common people who had gathered.

The Ghost Durbar: The Ceremony That Never Was

A fourth Durbar was planned. After King George V’s death, his successor, Edward VIII, announced his intention to hold a Durbar in Delhi in 1937. Even after his abdication, the plan was initially kept alive for the new king, George VI. However, the political landscape of India had fundamentally changed.

The Indian National Congress, having gained significant political power in the 1_937 provincial elections, made it clear they would boycott any such event and refuse to allocate funds. Leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru publicly advised that if the British wanted to protect their king from “untoward incidents,” they should simply keep him in England. The Viceroy, Lord Linlithgow, recognized that a Durbar held in a climate of such open political hostility would be a fiasco. Citing financial constraints and the tense political situation, the Durbar was first “postponed” and then quietly abandoned forever. The spectacle of imperial power could no longer be staged in a nation that was confidently marching towards independence.

The Enduring Legacy: More Than Just a Memory

What, then, is the legacy of the Delhi Durbars? On one hand, they were the ultimate expression of imperial dominance—a powerful tool of propaganda designed to cement British rule through overwhelming spectacle. They were a performance of power, meant to remind the Indian princes of their subordinate status and the Indian people of the might of the Raj.

What, then, is the legacy of the Delhi Durbars? On one hand, they were the ultimate expression of imperial dominance—a powerful tool of propaganda designed to cement British rule through overwhelming spectacle. They were a performance of power, meant to remind the Indian princes of their subordinate status and the Indian people of the might of the Raj.

Yet, they had a complex and often unintended legacy. By bringing together rulers and people from every corner of the subcontinent, they inadvertently fostered a greater sense of a shared Indian identity. They became a stage not only for imperial pomp but also for nascent nationalist expression.

Today, the physical remnants of this era can still be seen. Coronation Park in Delhi, where these grand events were held, is now a public park. The thrones used by King George V and Queen Mary are on display at Rashtrapati Bhavan, the residence of the President of India. These relics serve as silent witnesses to a time when Delhi was the stage for one of the most audacious political theatres in modern history, reflecting the spectacular rise, confident zenith, and inevitable decline of the British Empire in India.

1877 Durbar

- Viceroy Lytton proclaimed Queen Victoria as Empress, formalizing Crown Rule.

- Held during the Great Famine; featured the first call for equal rights by G.V. Joshi.

1903 Durbar

- Viceroy Curzon’s grand spectacle for King Edward VII’s coronation to display peak imperial power.

- The King did not attend; modern film was used for widespread propaganda.

1911 Durbar

- King George V attended; announced capital shift to Delhi and annulment of the Bengal Partition.

- The Gaekwar of Baroda’s gesture became a famous public symbol of dissent.

Cancelled Durbar (1937-38)

- Planned for King George VI under Viceroy Lord Linlithgow.

- Cancelled due to strong opposition from the Indian National Congress, marking the decline of British authority.

Loved this article? Go to Learning EDGE+ Page↗️