The Gupta Empire: Uncovering the Legacy of India’s Golden Age

Have you ever wondered what it takes to call an era a “Golden Age”? Is it about military might, sprawling territories, or immense wealth? Or is it something more profound—a period when art, science, and philosophy reach a breathtaking zenith, shaping the culture of a nation for a millennium to come? The story of the Gupta Empire, which flourished from the early 4th to the mid-6th century CE, invites us to explore this very question. Emerging from the political fragmentation that followed the Kushan and Satavahana empires, this dynasty didn’t just unite a vast portion of the Indian subcontinent; it presided over an unprecedented cultural efflorescence. This was the time of the mathematical genius Aryabhata, who gave the world the concept of zero; the literary brilliance of Kalidasa, whose plays and poems are cherished even today; and the creation of sublime art that set the standard for centuries. But was this Golden Age truly golden for everyone? Let’s journey back in time to uncover the realities of this remarkable period, from its mysterious origins and powerful rulers to its magnificent achievements and eventual decline.

Have you ever wondered what it takes to call an era a “Golden Age”? Is it about military might, sprawling territories, or immense wealth? Or is it something more profound—a period when art, science, and philosophy reach a breathtaking zenith, shaping the culture of a nation for a millennium to come? The story of the Gupta Empire, which flourished from the early 4th to the mid-6th century CE, invites us to explore this very question. Emerging from the political fragmentation that followed the Kushan and Satavahana empires, this dynasty didn’t just unite a vast portion of the Indian subcontinent; it presided over an unprecedented cultural efflorescence. This was the time of the mathematical genius Aryabhata, who gave the world the concept of zero; the literary brilliance of Kalidasa, whose plays and poems are cherished even today; and the creation of sublime art that set the standard for centuries. But was this Golden Age truly golden for everyone? Let’s journey back in time to uncover the realities of this remarkable period, from its mysterious origins and powerful rulers to its magnificent achievements and eventual decline.

The Mysterious Origins of the Guptas

Every great dynasty has a beginning, but the origins of the Guptas are shrouded in a captivating mystery. Unlike the Mauryas, whose lineage is more clearly documented, the early history of the Guptas is a puzzle that historians have pieced together from inscriptions, coins, and accounts of foreign travelers. The dynasty’s founder, a ruler named Gupta, is a somewhat enigmatic figure. So, where did this influential family come from?

The Geographical Debate: Magadha, Prayaga, or Bengal?

Scholars have proposed several theories about the original homeland of the Guptas.

One of the most prominent theories points to Magadha (in modern-day Bihar) as their ancestral home. This region had been the heart of the great Mauryan Empire and retained a legacy of political power. The evidence for this comes from the 7th-century Chinese traveler Yijing (I-tsing), who wrote about a ‘Maharaja Sri Gupta’ building a temple for Chinese pilgrims near a place called ‘Mi-li-kia-si-kia-po-no’ (believed to be Mrigashikhavana). Yijing places this temple about 40 yojanas east of Nalanda, which could situate it in either Bihar or Bengal. Furthermore, recent discoveries of silver coins in Bihar, bearing the name “Sri Gupta,” have added significant weight to the Magadhan origin theory. These coins suggest an independent monarch with the authority to issue currency, strengthening the claim that the Guptas began their political journey in this historic heartland.

Another compelling theory suggests that the Guptas originated in the lower Doab region of modern Uttar Pradesh, centered around Prayaga (modern Prayagraj). Proponents of this view argue that the majority of early Gupta inscriptions and coin hoards have been discovered in this area. The famous Allahabad Pillar inscription of Samudragupta, one of our primary sources for the dynasty’s history, is located here, suggesting the region’s central importance from an early stage.

A third theory, also drawing from Yijing’s account, places the Gupta homeland in the Bengal region. If the location of the temple he mentioned was further east, it would fall squarely within modern Bengal. While less widely accepted as their sole point of origin, it’s possible that the early Gupta kingdom was a stretch of territory extending from Prayaga in the west to northern Bengal in the east.

The Social Puzzle: Who Were the Guptas?

Just as their geography is debated, so is their social standing, or varna. The Gupta records themselves are silent on this matter.

One popular theory, advanced by historians like A.S. Altekar, posits that they were of Vaishya origin. This is based on ancient texts that prescribe the surname “Gupta” for members of the Vaishya varna, which was traditionally associated with trade, commerce, and agriculture. Historian R.S. Sharma further argued that as a mercantile class, they might have risen to power by resisting the oppressive taxes of previous rulers, eventually taking up arms and establishing their own kingdom.

However, this theory is not without its critics. They point out that the suffix ‘Gupta’ was used by people from various varnas, not just Vaishyas. It’s equally plausible that the dynasty’s name simply derived from its founder, Gupta.

Another school of thought, led by scholars like S.R. Goyal, suggests the Guptas were Brahmins. The primary evidence for this is their matrimonial alliances. The Gupta princess Prabhavatigupta, daughter of Chandragupta II, married into the Vakataka royal family, who were known to be Brahmins. Some inscriptions related to Prabhavatigupta mention her paternal gotra (clan) as “Dharana.” However, other interpretations of the same inscription suggest that “Dharana” might have been the gotra of her mother, making this evidence inconclusive.

Ultimately, the exact origins and varna of the Guptas remain a topic of scholarly debate. What is clear, however, is that from these humble and uncertain beginnings, a powerful dynasty was about to emerge and reshape the destiny of India.

The Rise of an Empire: The Early Rulers

The journey from a small principality to a sprawling empire was not instantaneous. It was a gradual ascent, built upon the strategic foundations laid by the first few rulers of the dynasty.

Sri Gupta and Ghatotkacha: The Forerunners

The origins of the illustrious Gupta Empire can be traced back to Sri Gupta (reigned c. 240–280 CE), the progenitor of the dynasty. Our primary source for his existence is the famous Prayagraj (Allahabad) Pillar inscription, commissioned by his great-grandson, the mighty emperor Samudragupta. This inscription reverently names Sri Gupta as the founder of the Gupta lineage. He, along with his son and successor, Ghatotkacha (reigned c. 280–319 CE), are both referred to with the title of Maharaja (महाराज), meaning “Great King.”

Their exact political status, however, remains a subject of scholarly debate. In the later, grander imperial era of the Guptas themselves, the title Maharaja was often used by feudatory rulers or subordinate chiefs who owed allegiance to a more powerful sovereign, the Maharajadhiraja (महाराजाधिराज), or “Great King of Kings.” This has led some historians to speculate that Sri Gupta and Ghatotkacha might have been vassals, perhaps serving under the authority of the declining Kushan Empire or another regional power like the Murundas.

However, this view isn’t conclusive. In the politically fragmented landscape of pre-Gupta India, the title Maharaja was also used by independent, albeit minor, sovereigns. Therefore, it’s equally possible that the early Guptas were independent rulers of a small kingdom, likely centered around Magadha in modern Bihar. Further evidence from the 7th-century Chinese traveler I-tsing suggests that a king named ‘Che-li-ki-to’—widely identified as Sri Gupta—built a temple for Chinese pilgrims near Mṛgaśikhāvana. This indicates a degree of autonomy and regional influence.

What is undeniable is that their power and prestige were significantly less than that of the rulers who would follow. Sri Gupta and Ghatotkacha were the crucial forerunners who laid the groundwork. They established a political foothold and consolidated their power over a modest territory, creating a stable base. They were the ones who lit the spark of ambition; their successor, Chandragupta I, would be the one to fan it into the blazing fire of an empire.

Chandragupta I: The Empire Builder

The true architect and founder of the Gupta Empire’s imperial lineage was Chandragupta I, who reigned from approximately 319 to 335 CE. While his predecessors, Sri Gupta and Ghatotkacha, laid the initial groundwork, it was Chandragupta I’s political acumen that elevated the dynasty from a local principality to a formidable kingdom. A visionary ruler, he understood that lasting power was built not just through conquest, but through strategic alliances. His most decisive political maneuver was his marriage to Kumaradevi, a princess from the powerful and ancient Lichchhavi clan.

The Lichchhavis were a highly respected oligarchical clan with a long history, controlling significant territories in the fertile region of modern-day Bihar and neighboring Nepal. This union was far more than a simple matrimonial alliance; it was a merger of prestige and power. By marrying into this esteemed lineage, Chandragupta I gained immense political legitimacy, social prestige, and crucial control over the resource-rich Gangetic plains. He was so proud and aware of the significance of this union that he issued a special series of gold coins—the famous ‘King and Queen’ type—which prominently depicted both him and his queen, a rare numismatic tribute that underscored the importance of the Lichchhavi connection to his imperial authority.

The Dawn of an Imperial Age

This newfound status and power allowed him to assume the grandiloquent title of Maharajadhiraja (“King of Great Kings”). This was a clear declaration of his imperial ambitions and a significant elevation from the humbler ‘Maharaja’ title used by his father and grandfather, signaling his suzerainty over lesser rulers. To further commemorate his ascent to power and the beginning of his dynastic rule, he is credited with starting the Gupta Era, a new calendar that commenced in 319-320 CE. Through these calculated moves, Chandragupta I successfully transformed a small principality into a fledgling empire, laying a solid foundation upon which his brilliant son, Samudragupta, would later build one of India’s greatest imperial structures.

The Question of Succession

According to the dynasty’s official inscriptions, Chandragupta I publicly nominated his son Samudragupta as his successor in a dramatic court assembly. However, the discovery of a cache of gold coins belonging to an obscure ruler named Kacha has introduced a slight wrinkle into this straightforward narrative. The Kacha coins are stylistically very similar to Samudragupta’s early issues, leading some scholars to believe that ‘Kacha’ was simply another name or an early title for Samudragupta himself. Conversely, other historians suggest Kacha might have been an elder brother or a rival claimant who briefly seized the throne after Chandragupta I’s death, only to be deposed by Samudragupta. This small numismatic mystery offers a fascinating glimpse into the potential court intrigues and succession struggles that often accompanied a transfer of power in ancient kingdoms.

Samudragupta: The Napoleon of India

If Chandragupta I was the architect, his son Samudragupta (reigned c. 335–375 CE) was the master conqueror who expanded the empire to its formidable size. His reign is a saga of relentless military campaigns, brilliant statesmanship, and a deep appreciation for the arts. Our most detailed source of information about him is the magnificent Allahabad Pillar inscription (also known as the Prayaga Prashasti), a panegyric composed by his court poet and minister, Harisena. This inscription, etched onto a pillar that also bears the edicts of Ashoka, paints a vivid picture of a ruler who was both a fierce warrior and a cultured king.

The Grand Military Campaigns

Harisena’s prashasti meticulously lists Samudragupta’s conquests, which can be categorized into several distinct campaigns, showcasing a sophisticated and multi-pronged imperial strategy.

- Conquests in Aryavarta (The Northern Heartland): The inscription boasts that Samudragupta “violently uprooted” several kings of Aryavarta, the core region of northern India. These included rulers of the Naga dynasty, who were powerful chieftains in the Ganga valley. By defeating them, Samudragupta consolidated his direct control over the most fertile and populous parts of the subcontinent, including modern-day Uttar Pradesh and parts of Madhya Pradesh. This policy of complete annexation in the heartland ensured a secure and resource-rich core for his empire.

- The Southern Expedition (Dakshinapatha): Perhaps his most audacious campaign was his long march into southern India. The inscription lists twelve rulers of Dakshinapatha whom he defeated. Tracing his probable route, it seems he moved through the forest tracts of central India, reached the eastern coast in Odisha, and then marched south along the Bay of Bengal, perhaps as far as Kanchipuram, the capital of the Pallavas.

However, Samudragupta’s policy here was remarkably different from his approach in the north. Instead of annexing these distant kingdoms, which would have been difficult to administer, he adopted a pragmatic three-fold policy known as grahaṇa-mokṣa-anugraha:- Grahaṇa (capturing the enemy).

- Mokṣa (liberating him).

- Anugraha (favouring him by reinstating him in his kingdom).

- In essence, he defeated these kings, took tribute from them, and then allowed them to rule their territories as his vassals. This was a masterstroke of diplomacy, turning potential enemies into subordinate allies and ensuring the flow of wealth to the Gupta treasury without the burden of direct administration.

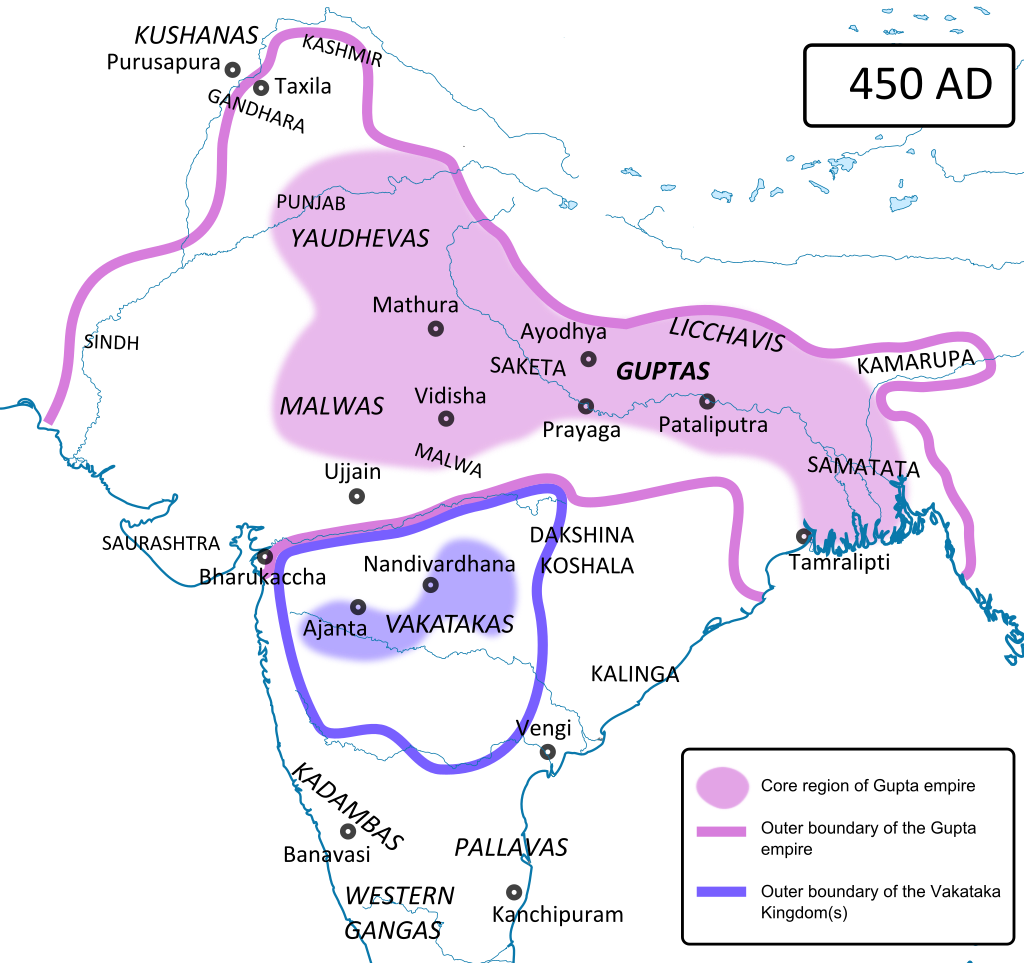

- Subjugation of Frontier States and Forest Tribes: The inscription also mentions that rulers of several frontier kingdoms and tribal republics paid him tribute, obeyed his orders, and performed obeisance. These included kingdoms on the periphery like Samatata (in southeastern Bengal), Davaka (in Assam), Kamarupa (modern Assam), and the kingdoms of Nepal and Karttripura (in the Himalayan foothills). It also lists several tribal republics of ancient India, such as the Malavas, Arjunayanas, Yaudheyas, and Madrakas in the Punjab and Rajasthan regions. By bringing them into his sphere of influence, Samudragupta created a secure buffer zone around his core territories.

Diplomatic Relations with Foreign Powers

Harisena’s account extends Samudragupta’s influence even beyond the borders of India. It claims that foreign kings, including the Daivaputra-Shahi-Shahanushahi (descendants of the Kushans in the northwest) and the ruler of Simhala (Sri Lanka), sought his favour. The inscription poetically states they offered him their daughters in marriage and sought permission to use the Garuda-stamped Gupta seal for administering their own territories.

While this is likely a court poet’s exaggeration, there is a kernel of truth. We know from Chinese sources that King Meghavarna of Sri Lanka did send an embassy to Samudragupta. However, his purpose was not to offer submission but to seek permission to build a monastery at Bodh Gaya for Sinhalese pilgrims. Samudragupta graciously granted this request. This incident shows that while not a direct vassal, the king of Sri Lanka recognized the Gupta emperor’s sovereignty over the land where the Buddha attained enlightenment. These relationships were more acts of diplomacy and mutual respect than outright subservience.

The Man Behind the Conqueror

Samudragupta was more than just a brilliant military strategist. The Allahabad inscription describes him as a compassionate ruler, a “king of poets” (Kaviraja), and a gifted musician. This claim is beautifully corroborated by his gold coins, some of which depict him seated and playing the veena, a stringed musical instrument.

A devout follower of Vaishnavism, he performed the ancient Ashvamedha (horse sacrifice) ceremony, a ritual undertaken by powerful kings to proclaim their undisputed imperial sovereignty. To commemorate this, he issued special gold coins. While he patronized Brahmanism and made generous donations, he was tolerant of other faiths, a hallmark of Gupta rule.

Samudragupta’s reign was foundational. He united a fragmented subcontinent through a clever mix of direct annexation, vassalage, and diplomacy, creating a vast and stable empire that became the crucible for a cultural renaissance.

An Interlude: The Curious Case of Ramagupta

History is often written by the victors, and sometimes, inconvenient rulers are edited out of the official narrative. For a long time, the Gupta chronicles jumped directly from Samudragupta to his illustrious son, Chandragupta II. However, literary and archaeological discoveries have unearthed the story of an elder brother, Ramagupta, whose brief and controversial reign forms a dramatic interlude.

Our primary source for this story is a 7th-century Sanskrit play, Devichandraguptam, by the playwright Vishakhadatta. Though the original play is lost, fragments survive as quotations in later works. The play tells a gripping tale: Ramagupta, faced with an invasion by a powerful Saka (Scythian) king, agrees to a humiliating peace treaty. The terms? To surrender his beautiful and virtuous queen, Dhruvadevi, to the Saka ruler.

Outraged by this dishonorable act, Ramagupta’s younger brother, Chandragupta, decides to take matters into his own hands. He disguises himself as the queen, enters the enemy camp accompanied by a band of elite soldiers dressed as female attendants, and assassinates the Saka king. He rescues Dhruvadevi, saving the dynasty’s honor. The aftermath is equally dramatic. Chandragupta, hailed as a hero, eventually kills his cowardly brother Ramagupta, marries Dhruvadevi, and ascends the throne.

For centuries, this was considered mere fiction. But then, archaeology came to the rescue. In the 20th century, three Jain statues were discovered at Durjanpur in Madhya Pradesh, with inscriptions explicitly naming Ramagupta as the ruling Maharajadhiraja. Alongside this, a large number of copper coins bearing his name were found in the Eran-Vidisha region.

This evidence confirms that Ramagupta was indeed a historical figure who ruled the empire, or at least a part of it. While the dramatic details of the play cannot be fully verified, the core events—a conflict with the Sakas and a subsequent power struggle between the two brothers—may well be true. This episode highlights the internal challenges the empire faced and sets the stage for the rise of one of its greatest rulers, a man who would finish the job of eliminating the Saka threat for good.

Chandragupta II Vikramaditya: The Zenith of the Golden Age

The man who ascended the throne after the Ramagupta affair was Chandragupta II (reigned c. 375–415 CE), a ruler who would become a legend. He adopted the title Vikramaditya, meaning “Brave as the Sun,” a name that became synonymous with justice, power, and cultural patronage in Indian folklore. His reign is widely regarded as the absolute peak of the Gupta Empire, a time of territorial expansion, economic prosperity, and an extraordinary flowering of art, literature, and science.

Final Conquests and Strategic Alliances

Chandragupta II inherited a vast empire, but one major rival power remained a thorn in its side: the Saka Western Kshatrapas. These rulers of Scythian origin had controlled the prosperous regions of Malwa, Gujarat, and Saurashtra for centuries. Their control over the western seaports gave them a monopoly on the lucrative trade with the Roman world.

In a long and decisive campaign that concluded around 409 CE, Chandragupta II finally vanquished the last Western Kshatrapa ruler, Rudrasimha III. This victory was a monumental achievement.

- It extended the Gupta Empire from coast to coast, giving it direct access to the wealthy western ports like Bharuch (Barygaza).

- The influx of trade revenue filled the imperial coffers, leading to unprecedented prosperity.

- He established a second capital at Ujjain in Malwa, which became a vibrant commercial and cultural hub of the empire.

Like his grandfather, Chandragupta II was also a master of matrimonial alliances. His most important diplomatic move was marrying his daughter, Prabhavatigupta, to Rudrasena II, the king of the Vakataka dynasty, which ruled a large swath of the Deccan plateau. When Rudrasena II died young, Prabhavatigupta ruled as regent for her minor sons, effectively bringing the Vakataka kingdom under the Gupta sphere of influence. This secured his southern flank and gave him a strategic advantage for his campaigns in the west. He also strengthened his own position by marrying Kuberanaga, a princess of the Naga lineage, further consolidating his power in central India.

The Court of Nine Jewels and Cultural Patronage

The crowning glory of Vikramaditya’s court was the legendary Navaratna (Nine Jewels), a council of nine brilliant minds who were masters of their respective fields. While modern historians debate whether all nine individuals were exact contemporaries, the tradition itself powerfully symbolizes the emperor’s immense patronage and the intellectual ferment of the age. This group represented the pinnacle of Indian scholarship.

The brightest star in this constellation was undoubtedly Kalidasa, often called the “Shakespeare of India” for his unparalleled mastery of Sanskrit poetry and drama. But the court included other luminaries as well:

- Amarasimha, the lexicographer who compiled the famous Sanskrit thesaurus, the Amarakosha.

- Varahamihira, a polymath who made significant contributions to astronomy, mathematics, and astrology with his work Brihat Samhita.

- Dhanvantari, the great physician considered a pioneer of Ayurveda.

- Other scholars like the grammarian Vararuchi and the astrologer Kshapanaka are also traditionally included in this esteemed circle

Kalidasa: The Apex of Sanskrit Literature

Kalidasa’s works are considered the epitome of classical Sanskrit literature, renowned for their lyrical beauty, emotional depth, and profound insight into human nature. His play Abhijnanashakuntalam (The Recognition of Shakuntala), a romantic tale of a king and a forest maiden, has captivated audiences for centuries and was one of the first Indian works to be translated into European languages. His epic poem Meghaduta (The Cloud Messenger) is a masterpiece of lyrical imagination, where a banished nature spirit sends a message to his lonely wife through a passing cloud. Other works like the dynastic epic Raghuvamsha and the mythological epic Kumarasambhava further cement his legacy as India’s greatest poet and dramatist.

An Efflorescence in Art and Architecture

The Gupta period witnessed a remarkable synthesis of artistic styles and the perfection of classical Indian art. The workshops at Mathura and Sarnath produced some of the most serene and spiritually profound Buddha images ever created. The Sarnath school, in particular, perfected a distinct style characterized by smooth bodies, transparent-looking drapery that clung to the form, and faces conveying a deep sense of inner peace and contemplation.

Hindu art also achieved iconic expression in magnificent stone sculptures and temple architecture. The Dashavatara Temple in Deogarh stands as a prime example. Though partially in ruins, its exquisitely carved relief panels are masterpieces. One famous panel depicts Vishnu Anantashayana—the deity reclining on the cosmic serpent Shesha, dreaming the universe into existence. This era was defined by a spirit of religious tolerance; Buddhist and Jain art flourished alongside Hindu art, all receiving support under the prosperous and stable umbrella of the Gupta state.

A Glimpse Through a Traveller’s Eyes: The Account of Faxian

We have a unique, firsthand account of what life was like under Chandragupta II, thanks to a Chinese Buddhist monk named Faxian (also known as Fa-Hien). He traveled through India between 405 and 411 CE on a pilgrimage to collect Buddhist scriptures. His travelogue provides a fascinating outsider’s perspective on the Gupta Empire at its height.

Faxian was deeply impressed by the peace, prosperity, and efficient administration he witnessed. He noted:

- Mild Governance: The government was lenient. The penal code was not harsh; most crimes were punished with fines. The death penalty was rare, and even for repeated rebellion, the punishment was often just the amputation of the right hand.

- Prosperity and Freedom: He described the people as numerous and happy. There was no household registration system, and people were free to move about as they wished. Those who cultivated the royal land paid a portion of the produce as tax.

- Social Harmony: Faxian observed that people across the country did not kill living creatures, drink intoxicating liquor, or eat onions or garlic. This suggests a strong influence of Buddhist and Brahminical ethics on public life. However, he did note the existence of “Chandalas” (untouchables), who were required to live separately and strike a piece of wood when entering a city so that others could avoid them, giving us a glimpse into the harsher realities of the caste system.

- Charitable Institutions: He was amazed by the well-run charitable institutions. In the capital, Pataliputra, he saw hospitals where the poor, destitute, and disabled could receive free care.

Faxian’s account paints a picture of a well-governed and prosperous society, largely peaceful and content. His writings remain one of the most valuable sources for understanding this Golden Age, providing a human touch to the grand narrative of kings and conquests.

The Successors: Preserving the Legacy

Maintaining a golden age is often harder than creating one. The successors of Chandragupta II faced the monumental task of preserving the vast and prosperous empire against growing internal and external threats.

Kumaragupta I: A Long and Peaceful Reign

Chandragupta II was succeeded by his son, Kumaragupta I (reigned c. 415–455 CE), who assumed the title Mahendraditya. He enjoyed a remarkably long and, for the most part, peaceful reign of forty years. The stability and prosperity of the empire under his rule are attested by the sheer variety and number of coins he issued, including rare types like the Ashvamedha coins, suggesting he also performed the horse sacrifice to affirm his imperial status.

Kumaragupta I’s most enduring legacy was in the field of education. He is credited with being the founder of the legendary Nalanda Mahavihara (great monastery), which would later evolve into the most famous university of the ancient world. Nalanda became a beacon of learning, attracting students and scholars from all over Asia for centuries.

However, the twilight of his reign was shadowed by a storm brewing on the horizon. Inscriptions mention a tribe called the Pushyamitras, from the Narmada valley, who rose in rebellion and posed a serious threat to the empire. More ominously, a new and formidable enemy appeared on the northwestern frontier: the Hunas (known as the Kidarites or Hephthalites). The task of dealing with these threats would fall to his son.

Skandagupta: The Last Great Gupta

Skandagupta (reigned c. 455–467 CE), son and successor of Kumaragupta I, is often hailed as the last of the great Gupta emperors. He was a warrior-king who spent much of his reign defending the empire his ancestors had built. He ascended the throne at a moment of grave crisis. The Bhitari pillar inscription provides a dramatic account of his struggles. It speaks of him spending a whole night sleeping on the bare earth while preparing for battle and describes how he single-handedly restored the fallen fortunes of the Gupta family.

His first major challenge was the Pushyamitra rebellion, which he successfully crushed. But the far greater danger came from the Hunas, a fierce nomadic people from Central Asia who were carving out a vast empire and had begun their devastating incursions into India. Around 455 CE, Skandagupta inflicted a crushing defeat on the Hunas, driving them back. For a brief period, he saved India from the fate that befell the Roman Empire, which crumbled under similar “barbarian” invasions. He proudly took the title of Vikramaditya to celebrate this monumental victory.

However, this victory came at a great cost. The continuous wars drained the imperial treasury. This economic strain is reflected in the coinage of his later years, which shows a decline in the purity of the gold. Skandagupta was the saviour of the empire, but his heroic efforts could only delay the inevitable decline.

The Long Sunset: Decline and Disintegration of the Empire

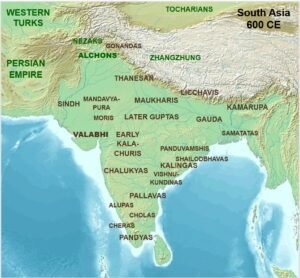

After the death of Skandagupta in 467 CE, the glorious sun of the Gupta Empire began its long and irreversible sunset. While the dynasty continued to rule for nearly another century, it was a shadow of its former self. A combination of internal weaknesses and relentless external pressures led to its gradual disintegration.

Weak Successors and Internal Strife

Skandagupta was followed by a line of less competent rulers, including Purugupta, Kumaragupta II, Budhagupta, and Narasimhagupta. The clear line of succession seems to have broken down, likely leading to internal power struggles and civil wars, which further weakened the central authority.

As the power of the central monarch waned, ambitious provincial governors and feudatory chiefs began to assert their independence.

- The Maitrakas of Vallabhi in Saurashtra established a powerful independent kingdom.

- The Maukharis rose to prominence in the region of Kannauj.

- The Later Guptas (a different dynasty with the same name) carved out a kingdom in Magadha, the very heartland of the empire.

The empire began to shrink, with vast territories in the west and central India slipping out of imperial control.

The Huna Invasions: The Final Blow

The most significant external factor in the empire’s downfall was the renewed and ferocious onslaught of the Hunas. In the late 5th century, a new wave of Alchon Huns, led by their ruthless chieftains Toramana and his son Mihirakula, broke through the Gupta defenses in the northwest.

By 500 CE, they had overrun Punjab and much of western India. Toramana established his rule in the region. His son, Mihirakula, was known for his extreme cruelty and his persecution of Buddhists. He destroyed monasteries and terrorized the population of northern India.

The Gupta emperors, though much weakened, continued to resist. An inscription from Eran (510 CE) mentions a Gupta ruler, Bhanugupta, fighting a great battle against the Huns. The final pushback came from a coalition of Indian rulers. The Gupta emperor Narasimhagupta Baladitya and, more prominently, Yashodharman, an ambitious ruler from Malwa, are credited with finally defeating Mihirakula around 528 CE and driving the Huns out of the Indian heartland.

The Aftermath and Legacy of the Decline

Though the Hunas were eventually defeated, their invasions had dealt a fatal blow to the Gupta Empire. The decades of warfare had exhausted its resources, shattered its administrative structure, and destroyed its trade networks. The Gupta Empire, already weakened by internal decay, simply could not recover. The last known ruler of the main Gupta line was Vishnugupta, who reigned around 540-550 CE. After him, the once-mighty empire faded into history.

Though the Hunas were eventually defeated, their invasions had dealt a fatal blow to the Gupta Empire. The decades of warfare had exhausted its resources, shattered its administrative structure, and destroyed its trade networks. The Gupta Empire, already weakened by internal decay, simply could not recover. The last known ruler of the main Gupta line was Vishnugupta, who reigned around 540-550 CE. After him, the once-mighty empire faded into history.

The collapse of the Guptas left northern India in a state of political disarray. Numerous smaller regional kingdoms emerged, and it would be nearly half a century before another powerful ruler, Harshavardhana of Kannauj, would attempt to restore some semblance of imperial unity. The Huna invasions had a lasting impact, disrupting the old trade routes with Central Asia and Europe and contributing to a decline in urban culture. In a sense, this period marked the end of Classical India and the beginning of the early medieval era.

The Machinery of Empire: Gupta Administration and Society

The stability and longevity of the Gupta Empire were not just due to its powerful emperors but also to its well-organized administrative machinery and a vibrant, structured society.

A Hierarchical Administration

The Gupta administration was less centralized than that of the Mauryas but was highly effective. It followed a clear top-down hierarchical structure.

- The King and Central Government: At the apex of the administration was the king, who adopted majestic titles like Maharajadhiraja (King of Great Kings), Parameshvara (Supreme Lord), and Parama-bhattaraka (Supreme Sovereign). Kingship was hereditary, but the rule of primogeniture (the eldest son inheriting the throne) was not always followed, sometimes leading to succession disputes. The king was assisted by a council of ministers (Mantriparishad) and a host of high-ranking officials. Key posts included the Sandhivigrahika (Minister of Peace and War) and the Kumaramatyas, a cadre of elite officers who could be appointed to various posts, including provincial governors.

- Provincial and District Administration: The empire was divided into provinces, known as Bhukti or Desha. Each province was placed under the charge of a governor, usually called an Uparika. Provinces were further subdivided into districts, known as Vishayas, which were governed by a Vishayapati. The district administration was not purely bureaucratic; it involved significant local participation. The Vishayapati was assisted by an advisory council (Adhikarana) composed of local representatives, including the chief banker (Nagarasreshthi), the leader of the merchant caravans (Sarthavaha), the chief artisan (Prathama-kulika), and the chief scribe (Prathama-kayastha).

- Local Governance: Below the district level were smaller units like the Vithi. The village (grama) remained the basic unit of administration. It was managed by a headman (Gramika or Gramadhyaksha), who was assisted by a village council of elders.

Economy: Agriculture, Trade, and Coinage

The economy was predominantly agrarian. Land revenue was the primary source of the state’s income, typically fixed at one-sixth of the produce (bhaga). The state also derived income from various other taxes (bhoga, kara).

Trade and commerce flourished. The conquest of the western coast opened up maritime trade with the Mediterranean and the Middle East, while overland routes connected India with Central Asia and China. Inland trade was facilitated by a network of rivers and roads, with merchants and artisans organized into powerful guilds (shrenis). These guilds functioned like modern corporations, with their own rules, finances, and even militias.

The Guptas issued a large number of beautiful coins. The most common were the gold coins, known as Dinaras, which are remarkable for their artistic merit, depicting kings in various poses—as archers, lion-slayers, or musicians. They also issued silver coins, mainly for their western territories, and copper coins for local transactions.

Society, Religion, and the Varna System

Gupta society was structured according to the traditional four-fold varna system (Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, Shudra). However, as Faxian’s account shows, the system was becoming more rigid, particularly with the hardening of rules regarding untouchability for groups like the Chandalas.

The position of women saw a decline compared to earlier periods. They were generally considered subordinate to men and were expected to be devoted to their husbands. Early marriage was common, and they were denied access to formal education and public life. However, they had rights to certain kinds of property (stridhana). The first epigraphic evidence for the practice of Sati (a widow immolating herself on her husband’s funeral pyre) comes from this period, found in an inscription at Eran dated 510 CE.

In terms of religion, the Gupta period was a time of Hindu resurgence. The Vedic sacrificial religion was gradually replaced by a more devotional, Puranic Hinduism centered on the worship of deities like Vishnu and Shiva. The Guptas themselves were primarily Vaishnavas (worshippers of Vishnu) and used the mythical bird Garuda as their royal emblem. This period saw the construction of the first structural temples and the canonisation of major texts like the Mahabharata, Ramayana, and various Puranas.

Despite their personal faith, the Gupta rulers were remarkably tolerant of other religions. Buddhism continued to thrive, with great centers of learning like Sanchi and Nalanda flourishing under their rule. Jainism also found patronage, particularly in western India. This policy of religious pluralism contributed significantly to the social harmony and cultural creativity of the age.

The Lasting Legacy: A True Golden Age?

The Gupta Empire may have collapsed, but its legacy endured, profoundly shaping the course of Indian civilization. The sheer scale and quality of its achievements in diverse fields are why this era is often called the Classical or Golden Age of India.

Science and Mathematics

This was an age of revolutionary scientific thought.

- Mathematics: The most significant contributions were the development of the decimal system and the invention of the concept of zero (shunya), which transformed mathematics worldwide. The mathematical genius Aryabhata, in his work Aryabhatiya, calculated the value of Pi to a remarkable accuracy (3.1416) and the length of the solar year (365.358 days). He also correctly stated that the Earth is a sphere that rotates on its axis and revolves around the Sun, causing day, night, and eclipses.

- Astronomy: Varahamihira, another brilliant mind, wrote the Pancha Siddhantika, a compendium of five astronomical systems.

- Medicine: The famous medical texts of Charaka and Sushruta were likely redacted and compiled in their final form during this period. The Sushruta Samhita is a detailed manual on surgery, describing complex procedures like cataract surgery and plastic surgery.

- Metallurgy: The technical skill of Gupta metallurgists is epitomized by the famous Iron Pillar of Delhi. Standing in the Qutub complex, this 1,600-year-old pillar has remained virtually rust-free, a testament to the advanced metallurgical knowledge of the time.

Literature, Art, and Architecture

- Literature: This was the golden age of Classical Sanskrit literature. The court of Chandragupta II shone with the works of Kalidasa. Other major literary works from this period include the Mrichchhakatika (The Little Clay Cart) by Shudraka, a realistic social drama, and the Kama Sutra by Vatsyayana, a comprehensive treatise on human sexuality and social life. The Panchatantra, a collection of fables that traveled across the world, was also compiled during this time.

- Architecture: The Gupta period marks the beginning of free-standing Hindu temple architecture. Early temples were simple structures, consisting of a flat-roofed, square sanctum (garbhagriha). A prime example is Temple No. 17 at Sanchi. The Dashavatara Temple at Deogarh (in modern Uttar Pradesh) represents a later stage, being one of the first temples to feature a shikhara (tower) and exquisite sculptural panels depicting scenes from Hindu mythology.

- Sculpture: Gupta sculpture is renowned for its grace, simplicity, and spiritual tranquility. The seated Buddha image from Sarnath, with its serene expression and perfect balance, is considered a masterpiece of world art. Similarly, Hindu sculptures, like the monumental relief of Vishnu as the boar incarnation (Varaha) at the Udayagiri Caves, display immense power and dynamism.

- Painting: The pinnacle of Gupta-era painting is preserved on the walls of the Ajanta Caves in Maharashtra. Though created under Vakataka patronage, these murals reflect the classical Gupta style. They depict scenes from the life of the Buddha (Jataka tales), royal processions, and daily life with extraordinary vibrancy, emotional depth, and technical finesse.

A Concluding Reflection

So, was the Gupta era a “Golden Age”? If we measure it by its contributions to mathematics, science, literature, and art—contributions that have left an indelible mark on human civilization—the answer is a resounding yes. It was a period of immense intellectual and creative energy, marked by stability, prosperity, and a sophisticated culture.

However, it is also important to view this with nuance. The “gold” of this age did not shine equally on everyone. The rigidities of the caste system were hardening, and the status of women was in decline. The prosperity described by travelers like Faxian was likely concentrated in the cities and among the upper classes.

Yet, the Gupta period remains a benchmark in Indian history. It established a cultural template—in art, religion, literature, and statecraft—that would influence the subcontinent for centuries. It was a time when the Indian genius soared to new heights, creating a legacy that continues to inspire and awe the world.

SHORT NOTES

The Gupta Empire (c. 320–550 CE): India’s Classical Age

The Gupta dynasty established India’s “Classical Age,” an era of remarkable achievements that profoundly shaped Indian culture. Emerging from the political vacuum left by the Kushans and Satavahanas, the Guptas, who were likely of Vaishya origin, forged an empire from their heartland in the fertile Gangetic plains (around Prayag). Their power was built on a strong economic base of agricultural surplus, control over iron ore deposits in central India, and command of lucrative northern trade routes.

The Great Emperors

Chandragupta I (c. 319–335 CE):

Considered the true founder of the empire’s imperial status. His most significant move was a strategic marriage to the Lichchhavi princess Kumaradevi. This alliance, commemorated on special gold coins, gave his non-Kshatriya dynasty immense prestige and security.

He was the first to assume the grand title Maharajadhiraja (Great King of Kings) and established the Gupta Era commencing in 319 CE.

Samudragupta (c. 335–380 CE):

A military genius often called the “Napoleon of India.” His extensive conquests are detailed in the Prayag Prashasti (Allahabad Pillar Inscription), composed by his court poet Harishena.

Conquest Strategy:

North (Aryavarta): He followed a ruthless policy of complete annexation, defeating nine rulers to secure the imperial heartland.

South (Dakshinapatha): He showed brilliant statesmanship with a policy of dharma-vijaya (righteous conquest). After defeating twelve rulers, he liberated and reinstated them as tribute-paying vassals, realizing direct rule over the distant south was impractical.

He was a versatile ruler who patronized scholarship and was an accomplished musician, famously depicted playing the vina (lute) on his coins.

Chandragupta II (Vikramaditya) (c. 380–412 CE):

The empire reached its absolute zenith under his rule.

Diplomacy & Conquest: He secured the Deccan through a matrimonial alliance with the powerful Vakataka dynasty by marrying his daughter, Prabhavati Gupta, to their king. This secured his southern flank for his greatest military achievement: the final defeat of the Shaka Kshatrapas in western India.

Economic Impact: This victory gave the Guptas control of prosperous western sea ports like Broach (Bharuch), opening up a floodgate of profitable trade with the Roman world. The resulting wealth made Ujjain a vibrant commercial and cultural hub, effectively a second capital.

His court was famed for its Navaratnas (Nine Gems), a group of nine extraordinary scholars, including the great poet Kalidasa.

Administration and Society

Governance: The Gupta administration was decentralized, in contrast to the rigid central control of the Mauryas. Provincial governors and local chiefs held significant power, and conquered kings were often allowed to rule as feudatories.

Social Structure: Society became more rigid during this period. The caste system hardened, and the condition of untouchables (chandalas) worsened significantly, a fact recorded by the visiting Chinese pilgrim Fa-hsien. The status of women also declined compared to earlier eras, with inheritance rights curtailed and the first evidence of the practice of Sati appearing.

Judiciary: The Guptas had a well-developed judicial system. For the first time, civil and criminal laws were clearly defined and separated.

The Golden Age: Culture & Science

The Gupta era is celebrated for its unparalleled intellectual and artistic output.

Science & Mathematics:

The concept of zero and the decimal system were invented, forming the foundation of the modern numerical system.

The great astronomer Aryabhata wrote the Aryabhatiya, where he proposed that the Earth is a sphere that rotates on its own axis and correctly explained the causes of solar and lunar eclipses. He also calculated the value of Pi and the length of the solar year with remarkable accuracy.

Literature: Sanskrit literature reached its peak. Kalidasa, the “Shakespeare of India,” wrote timeless plays like Abhijnanashakuntalam and epic poems like Meghaduta. Other key works include the Panchatantra stories and the Kama Sutra.

Art & Architecture: This period saw the beginning of free-standing Hindu temple architecture, moving away from rock-cut caves. The Dashavatara Temple at Deogarh is a prime example. Gupta sculpture, particularly the serene Buddha images from Sarnath, is considered a high point of Indian art.

Decline and Fall of the Empire

The collapse of the Gupta Empire was a gradual process caused by several converging factors.

External Invasions: Relentless and repeated attacks by the Hunas (a branch of the Huns) from Central Asia exhausted the empire’s military and financial resources. Emperor Skandagupta is celebrated for inflicting a crushing defeat on them early on, but his weaker successors could not hold them back.

Internal Fragmentation: As the authority of the central rulers weakened, powerful provincial governors and feudatory chiefs, most notably Yashodharman of Malwa, began to assert their independence, carving out their own kingdoms.

Economic Crisis: The loss of western India to the Hunas cut off the immense revenues from sea trade. This severe economic strain is confirmed by physical evidence, such as the debasement of later Gupta gold coinage (which had drastically reduced gold purity) and the recorded migration of a guild of silk weavers from Gujarat in 473 CE, indicating a collapse in the luxury goods trade.

By c. 550 CE, the once-mighty empire had crumbled, though its cultural and scientific legacy endured to define classical India.

COSMOS XTRA+

Timeline of the Gupta Empire

c. 240–280 CE: The reign of Sri Gupta, the founder of the Gupta dynasty.

c. 280–319 CE: The reign of Ghatotkacha, son of Sri Gupta.

c. 319–335 CE: The reign of Chandragupta I, the true architect of the empire who started the Gupta Era.

c. 335–375 CE: The reign of Samudragupta, a brilliant military conqueror who vastly expanded the empire’s territory.

Harisena: Samudragupta’s court poet and minister who detailed his conquests.

c. 375 CE (approx.): The brief and controversial reign of Ramagupta, elder brother of Chandragupta II.

Vishakhadatta: A later playwright who chronicled the story of Ramagupta in his play Devichandraguptam.

c. 375–415 CE: The reign of Chandragupta II Vikramaditya, under whom the empire reached its absolute peak.

Kalidasa: The legendary poet and playwright who was the brightest of the emperor’s “Nine Jewels.”

405–411 CE: The journey of Faxian, a Chinese Buddhist monk who documented the peace and prosperity of the empire.

c. 409 CE: Chandragupta II conquers the Western Kshatrapas, defeating their last ruler, Rudrasimha III.

c. 415–455 CE: The reign of Kumaragupta I, who had a long, peaceful reign and founded the Nalanda monastery.

c. 455–467 CE: The reign of Skandagupta, the warrior-king hailed as the last great Gupta emperor for defeating the Huna invasion.

Late 5th Century CE: Renewed Huna invasions are led by their ruthless chieftain Toramana.

c. 510 CE: An inscription mentions a Gupta ruler, Bhanugupta, fighting a major battle against the Huns.

c. 528 CE: The Huna leader Mihirakula (son of Toramana) is finally defeated by a coalition including Gupta emperor Narasimhagupta Baladitya and the Malwa ruler Yashodharman.

c. 540–550 CE: The reign of Vishnugupta, the last known ruler of the imperial Gupta line before its collapse.

PRACTICE QUES

1. Which of the following statements regarding the Enfield rifle cartridge controversy is correct?

- The cartridge was greased with cow and pig fat.

- Soldiers had to bite the cartridge open with their teeth.

- British officers confirmed the presence of animal fat.

Explanation: One of the major immediate causes of the revolt was the introduction of the Enfield rifle. The cartridges for this rifle were greased with animal fat, specifically from cows and pigs—offensive to both Hindus and Muslims. Soldiers had to bite the cartridges open, and this act was seen as a direct threat to their religion. Although the British denied it, the belief spread rapidly among the sepoys and caused mass resentment, ultimately acting as the spark for the uprising.

Correct Answer: A

2. Which of the following was a political cause of the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: The British expansionist policies, especially under Lord Dalhousie, alienated Indian rulers. The Doctrine of Lapse allowed the British to annex any princely state without a male heir. Under the Subsidiary Alliance system, Indian states lost their sovereignty. The symbolic removal of Mughal power, like denying Bahadur Shah Zafar the right to be called emperor, deeply offended Indian sentiment. These moves collectively fostered a climate of political unrest.

Correct Answer: D

3. With reference to the Revolt of 1857, which of the following pairs is correctly matched?

- Awadh — Begum Hazrat Mahal

- Jhansi — Kunwar Singh

- Kanpur — Bahadur Shah Zafar

Explanation: Begum Hazrat Mahal took charge of the revolt in Awadh after the annexation of the region. Jhansi was led by Rani Lakshmibai, not Kunwar Singh—he led the revolt in Bihar. Kanpur was under the leadership of Nana Saheb and Tantia Tope, while Bahadur Shah Zafar was declared the symbolic leader of the revolt in Delhi. Understanding the correct leaders helps in mapping the geographic spread and intensity of the revolt.

Correct Answer: A

4. Which of the following were social-religious causes of the Revolt of 1857?

- Abolition of Sati

- Legalization of widow remarriage

- Conversion of Indians to Christianity

- Suppression of traditional customs

Explanation: Many Indians saw the social reforms introduced by the British as intrusive and disrespectful to traditional beliefs. Though practices like Sati were regressive, their abolition and the legalization of widow remarriage were seen by conservatives as British attempts to interfere in Indian culture. Moreover, the spread of Christian missionaries and conversions added to fears that the British intended to impose Christianity, leading to a strong cultural backlash.

Correct Answer: D

5. Who among the following was the leader of the rebellion in Jhansi during the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi was one of the most prominent and fearless leaders of the 1857 revolt. She led her troops with valor and resilience, famously defending the city of Jhansi against the British forces. After the fall of Jhansi, she continued to fight for the cause of independence and became an iconic figure in Indian history, symbolizing courage and resistance.

Correct Answer: A

6. Which of the following actions by the British government angered the sepoys and led to the rebellion?

- Introduction of the Enfield rifle

- Annexation of Indian territories

- Outlawing of traditional practices

- Imposition of heavy taxes

Explanation: The British actions—such as the introduction of the Enfield rifle, which required sepoys to bite a cartridge greased with animal fat, and the annexation of several Indian states under the Doctrine of Lapse—angered many Indians. Additionally, the British government's interference in traditional practices, such as outlawing Sati and introducing social reforms, created resentment. This widespread dissatisfaction culminated in the 1857 uprising. While heavy taxes were also a cause of discontent, the initial trigger and the listed items 1, 2, and 3 were very direct causes of the rebellion.

Correct Answer: B

7. Which of the following territories did NOT witness major revolts during the 1857 uprising?

Explanation: While regions like Delhi, Kanpur, and Lucknow saw significant uprisings during the 1857 Revolt, the southern parts of India, including Madras (present-day Chennai), did not actively participate. The revolt was mainly centered in North and Central India, where widespread resistance against British rule occurred, led by local rulers and military personnel.

Correct Answer: C

8. Which of the following was the last stronghold of the Indian rebels during the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: Delhi was the last major stronghold of the Indian rebels during the 1857 Revolt. The city had been declared the center of the rebellion with Bahadur Shah Zafar as its symbolic leader. The British forces laid siege to Delhi for several months before finally capturing it in September 1857, marking a significant turning point and effectively the fall of the organized rebellion.

Correct Answer: C

9. Who was the British commander who played a major role in suppressing the revolt in Kanpur?

Explanation: Sir Colin Campbell, along with Sir Henry Havelock, played a key role in recapturing Kanpur from the rebel forces. After the fall of the city to Nana Saheb’s forces, Campbell led the British army in a series of battles that ultimately restored British control over the region. His role in suppressing the revolt earned him recognition, but also controversy due to the brutal repression of the rebels.

Correct Answer: B

10. The last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was exiled to which location after the suppression of the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: Bahadur Shah Zafar, after the suppression of the 1857 Revolt, was captured by the British. The British, aiming to remove him as a figurehead for further uprisings, exiled him to Rangoon (present-day Yangon) in Burma (Myanmar). His exile marked the effective end of the Mughal Empire and the beginning of direct British rule in India.

Correct Answer: C

11. The Revolt of 1857 is also known as which of the following in Indian history?

Explanation: The Revolt of 1857 is known by several names. In India, it is often referred to as the 'First War of Independence,' recognizing it as the first significant attempt by Indians to challenge British colonial rule. The British called it the 'Sepoy Rebellion,' due to the primary role of Indian soldiers (sepoys) in the military. It is also referred to as a 'mutiny' by some historians, particularly British, who viewed it as a rebellion confined to the military ranks rather than a widespread national uprising.

Correct Answer: D

12. Which of the following was the immediate cause of the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: The introduction of the Enfield rifle and its controversial greased cartridges was the immediate trigger for the Revolt of 1857. This sparked widespread anger among the sepoys, as they had to bite open the cartridges, which were allegedly made of cow and pig fat. This deeply offended both Hindu and Muslim soldiers, leading to a large-scale uprising against British rule. While the other options were underlying causes, the cartridge issue was the spark.

Correct Answer: A

13. Which of the following leaders of the Revolt of 1857 is known for his leadership in Bihar?

Explanation: Kunwar Singh was a prominent leader in Bihar during the 1857 revolt. A Rajput ruler, he led a determined resistance against British forces in Bihar and neighboring regions. Despite his age and limited resources, he showed remarkable courage and strategic acumen in battles. He is considered one of the major leaders of the revolt in Eastern India.

Correct Answer: B

14. Which city witnessed a brutal massacre of Indian rebels after their surrender during the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: After the fall of Kanpur, the British forces under Sir Colin Campbell were involved in brutal actions against Indian rebels and civilians. This incident, sometimes referred to as the 'Cawnpore massacre' (though the term typically refers to the killing of British women and children by rebels), highlights the extreme violence that occurred in the city. The subsequent British reprisal was also harsh. While the question phrasing is ambiguous about *which* massacre, Kanpur was indeed a site of extreme violence involving both sides. The British forces' actions after re-taking the city were particularly harsh.

Correct Answer: B

15. Who among the following was not associated with the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India, was not associated with the Revolt of 1857. He was born in 1889, long after the events of 1857. On the other hand, Mangal Pandey was one of the first to rise against the British at the Barrackpore cantonment, and Tantiya Tope was a key military leader in the revolt. Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal emperor, played a symbolic role as the figurehead of the rebellion.

Correct Answer: D

16. What was the role of women in the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: Women played a significant and diverse role in the Revolt of 1857. Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi and Begum Hazrat Mahal of Awadh are prime examples of women who not only participated but also bravely led the rebellion in their respective regions. Beyond direct leadership, women also provided crucial logistical support, covert assistance, and inspired resistance.

Correct Answer: C

17. Which of the following was a consequence of the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: While the Revolt of 1857 did not immediately end British rule, it led to a significant shift in governance. The British East India Company's rule was abolished, and the direct administration of India was taken over by the British Crown through the Government of India Act, 1858. This marked the beginning of the British Raj and major administrative changes.

Correct Answer: B

18. Which of the following was NOT a key reason for the British to suppress the Revolt of 1857 so ruthlessly?

Explanation: The British ruthlessly suppressed the revolt primarily to re-establish their authority, deter future uprisings (by setting a harsh example), and punish those involved. Increasing British support among Indian rulers was an outcome of their *subsequent* policy (e.g., policy of 'paramountcy' and non-annexation) rather than a direct reason for the initial ruthless suppression, which actually alienated many. The suppression itself was more about force and control than about winning hearts and minds at that moment.

Correct Answer: D

19. The British strategy of dividing and ruling during the Revolt of 1857 mainly involved:

Explanation: The British successfully used the "divide and rule" policy by exploiting existing divisions and creating new ones. During the Revolt, they forged alliances with certain Indian rulers (like the Nizam of Hyderabad, the Sikhs, and the Gurkhas) who remained loyal or actively supported the British, using their forces and resources to suppress the rebellion. This was a crucial factor in the British victory.

Correct Answer: A

20. Who was the British officer responsible for the suppression of the Revolt of 1857 in Delhi?

Explanation: John Nicholson played a critical and decisive role in the suppression of the Revolt of 1857 in Delhi. He commanded the British forces during the siege and recapture of Delhi, though he was mortally wounded during the final assault. His military leadership and aggressive tactics were crucial in breaking the rebel resistance in the city.

Correct Answer: C

Discuss the immediate and underlying causes of the Revolt of 1857.

Evaluate the role of Indian sepoys in the initiation and spread of the Revolt of 1857.

To what extent can the Revolt of 1857 be called a national movement? Substantiate your answer.

Analyze the role played by different social groups in the Revolt of 1857.

Discuss the regional variations in the intensity and spread of the Revolt of 1857.

Examine the role of Indian leaders in mobilizing masses during the Revolt of 1857.

Critically evaluate the British response to the Revolt of 1857 and the military strategies used to suppress it.

What were the consequences of the Revolt of 1857 on British administrative policies in India?

Explain how the Revolt of 1857 influenced the future course of India’s freedom struggle.

Compare the Revolt of 1857 with earlier uprisings in India. What made 1857 unique?