Continental Drift Theory: Revisiting Alfred Wegener’s Revolutionary Theory

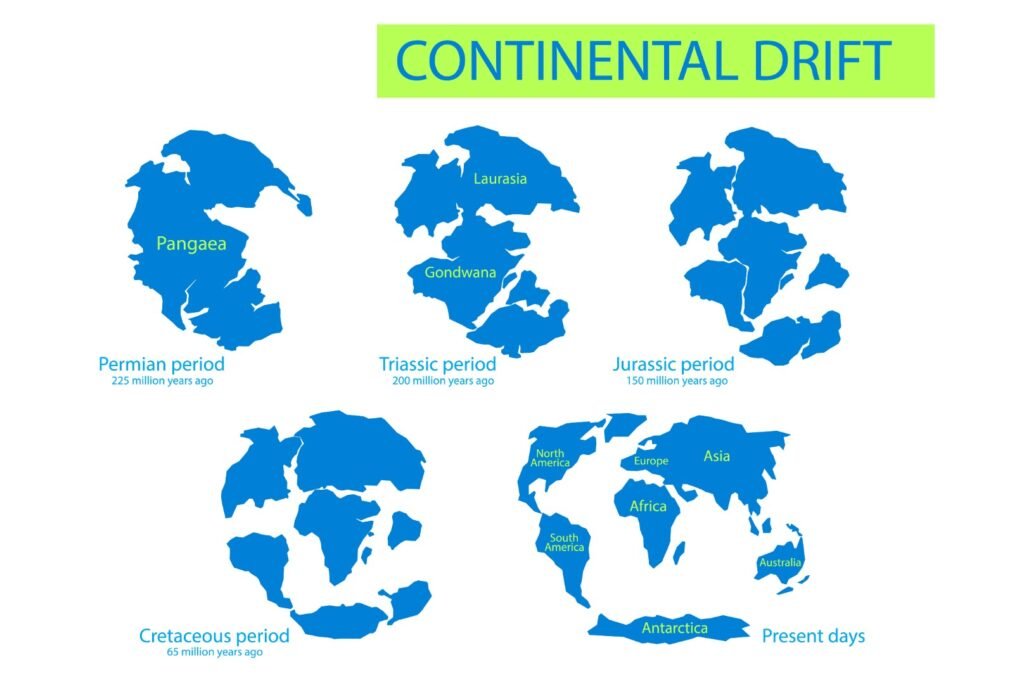

Home › Articles › हिंदी CONTINENTAL DRIFT THEORY: REVISITING ALFRED WEGENER’S REVOLUTIONARY THEORY Related toPhysical Geography Published on9 June 2025 Have you ever looked at a world map and noticed how the eastern coastline of South America seems to nestle perfectly into the western coast of Africa, almost like pieces of a giant jigsaw puzzle? This isn’t just a coincidence. It’s a clue to a revolutionary idea that, a century ago, turned the world of geology upside down. This is the story of the Continental Drift Theory, a concept proposed by a German meteorologist named Alfred Wegener. He suggested that our continents are not fixed but are constantly, albeit slowly, wandering across the face of the Earth.While his ideas were initially met with ridicule, they laid the foundation for our modern understanding of the dynamic planet we live on. So, let’s journey back in time and explore this groundbreaking theory. The Grand Idea: A World Once United In the early 1920s, Alfred Wegener put forth a bold hypothesis. He proposed that about 300 million years ago, all of the Earth’s continents were joined together in a single, colossal supercontinent. He named this landmass Pangaea, meaning “all lands” in Greek. This supercontinent was surrounded by a single, vast ocean called Panthalassa, or “all seas”. According to Wegener, Pangaea was not a permanent fixture. He suggested that it was split by a long, shallow sea called the Tethys Sea, which separated it into two smaller supercontinents: Laurasia to the north and Gondwanaland to the south. Then, around 200 million years ago, during the Mesozoic Era, these landmasses began to break apart and drift away from each other, eventually forming the continents as we know them today. The Driving Force: What Powered the Drift? One of the most challenging questions for Wegener was to explain what force could possibly be powerful enough to move entire continents in his Continental Drift Theory. He proposed two main mechanisms: Pole-fleeing Force: Wegener suggested that the Earth’s rotation creates a centrifugal force, which is strongest at the equator. He believed this force caused the continents to drift away from the poles and towards the equator. Tidal Force: He also theorized that the gravitational pull of the moon and the sun, which causes ocean tides, exerted a westward drag on the continents, causing them to drift. While these ideas were creative, they would later become the theory’s biggest weakness. Modern science has shown that these forces are far too weak to move continents. However, Wegener’s attempt to provide a mechanism, however flawed, was a crucial step in the right direction. The Trail of Clues: Evidence for The Continental Drift Theory Wegener was not just a dreamer; he was a meticulous scientist who gathered a wealth of evidence from different fields to support his theory. Let’s look at some of the compelling clues he presented. 1. Jigsaw Fit of Continents Example: Coastline of Brazil and West Africa One of the most visual and striking pieces of evidence for continental drift is the jigsaw-like fit of continents across the Atlantic Ocean. If we observe the eastern coast of South America, particularly Brazil, and compare it with the western coast of Africa, especially regions around Ghana, the coastlines align remarkably well. This fit is not just a surface coincidence; studies of the continental shelves—submerged extensions of continents—show an even more precise match. This suggests that these landmasses were once connected and later drifted apart due to tectonic movements. Scientific Insight:This observation served as one of Wegener’s earliest proofs, demonstrating that continents were not fixed but mobile over geological time scales. 2. Geological Evidence: Rock Types and Mountain Systems Example: The Gondwana Sedimentary System Another strong pillar supporting the theory lies in the continuity of rock formations across continents. The Gondwana system of sediments, which refers to geological layers laid down during the time of the ancient supercontinent Gondwanaland, is found across multiple present-day landmasses. India, South America (Brazil & Argentina), Africa (South Africa & Ghana), Australia, Antarctica, and Madagascar all exhibit matching sequences of Permo-Carboniferous glacial sediments. These rocks not only share similar mineral compositions but also reflect identical geological histories, such as glaciation events and the presence of specific fossils. Scientific Insight:Such identical geological patterns across continents that are now separated by vast oceans strongly point toward a common origin and later drift. 3. Paleontological Evidence: Fossils of Identical Species Example: Mesosaurus and Glossopteris Fossils Fossil records provide compelling evidence of past continental connectivity. For instance: Fossils of Mesosaurus, a small freshwater reptile, are found in both South America and Southern Africa, but nowhere else in the world. The reptile was not capable of swimming across oceans, implying the continents were once joined. Similarly, fossils of the ancient fern Glossopteris are widely found across India, South America, Africa, Antarctica, and Australia, reinforcing the idea of a shared landmass during the plant’s existence. Scientific Insight:These fossil distributions are difficult to explain unless the continents were once connected, allowing species to thrive across them. 4. Mineral and Natural Resource Distribution Example: Gold Deposits in Brazil and Ghana Another intriguing line of evidence is the occurrence of similar mineral resources in regions now separated by oceans. The gold-bearing rocks of Ghana (in West Africa) and Brazil (in South America) are geologically identical, in terms of both age and composition. These gold-rich formations formed under the same environmental conditions and time period when the two regions were part of the same continental block. Scientific Insight:This geochemical resemblance supports the theory that South America and Africa were once connected, forming a contiguous mineral-rich belt. 5. Paleoclimatic Evidence Example: Glacial Deposits in Tropical Regions Continental drift also explains ancient climatic anomalies. Rocks in India, South America, South Africa, and Australia show signs of glaciation, despite these regions now lying in warm tropical zones. The presence of glacial striations and tillite deposits from the Permo-Carboniferous period suggests that these continents were once located closer to the South Pole. Only after drifting to their present positions did

Continental Drift Theory: Revisiting Alfred Wegener’s Revolutionary Theory Read More »