THE Revolt of 1857: 1st Freedom Struggle That Ignited India's Quest for Independence

The Revolt of 1857 was a defining moment in India’s resistance against British rule. Often referred to as the First War of Indian Independence, it reflected deep-rooted dissatisfaction that had been simmering for years. From soldiers and peasants to local rulers, people from diverse backgrounds united against colonial oppression and exploitation.

The Revolt of 1857 was a defining moment in India’s resistance against British rule. Often referred to as the First War of Indian Independence, it reflected deep-rooted dissatisfaction that had been simmering for years. From soldiers and peasants to local rulers, people from diverse backgrounds united against colonial oppression and exploitation.

This chapter, which is very important for Modern History, explores the underlying causes of the revolt, both long-term and immediate, along with major events, key leaders, and the regions affected. It also covers how the British suppressed the rebellion and the far-reaching consequences that followed.

The Roots of Discontent Leading to the Revolt of 1857

The Revolt of 1857 was not a sudden outbreak of violence, but rather the culmination of years of resentment against British policies that had gradually eroded the traditional way of life in India. Various factors contributed to this simmering discontent, including the economic exploitation of the Indian population, the displacement of native rulers, the alienation of the Indian masses by the British administration, and the perceived threat to the social and religious fabric of Indian society. This section explores these underlying tensions in detail, shedding light on the various factors that contributed to the growing unrest.

The Indian economy had been heavily exploited by the British, who prioritized their own economic interests over the welfare of the Indian people. The introduction of the Permanent Settlement of 1793 disrupted traditional landholding patterns, forcing zamindars and peasants to pay exorbitant land revenues, often leading to widespread poverty and distress. This economic exploitation was further exacerbated by the commercialization of agriculture, which forced farmers to grow cash crops like indigo and cotton, leading to frequent famines and food shortages.

The political landscape of India was also significantly altered by British policies. The Doctrine of Lapse, introduced by Lord Dalhousie, allowed the British to annex any princely state where the ruler died without a male heir. This aggressive expansionist policy led to the annexation of several states, including Satara (1848), Sambalpur (1850), Jhansi (1854), and Nagpur (1853). The displacement of native rulers not only caused resentment among the princely states but also created a sense of insecurity among other rulers, who feared they might suffer the same fate.

The British administration was characterized by a sense of racial superiority, which alienated the Indian population. The judicial system was biased, favoring Europeans over Indians, and the British officials were often dismissive of Indian customs and traditions. The replacement of Persian with English as the official language and the imposition of English education further distanced the rulers from the ruled, creating a sense of alienation among the educated classes.

The British were also seen as a threat to the social and religious fabric of Indian society. The introduction of social reforms, such as the Abolition of Sati (1829), the Widow Remarriage Act (1856), and the encouragement of Western education, were perceived as attempts to Christianize India. The activities of Christian missionaries, coupled with the official support for their endeavors, led to widespread fear that the British were intent on undermining the religious practices of both Hindus and Muslims.

The early 19th century was marked by significant global events that influenced Indian sentiments. The defeat of the British in the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839-42) and the Crimean War (1853-56) showcased the vulnerability of the British Empire. These events, along with the rise of nationalist movements in Europe, inspired Indian intellectuals and leaders to believe that the British could be defeated, further fueling the discontent against colonial rule.

The 1857 Rebellion: Unravelling the Major Catalysts

Economic Causes: The Impact of Colonial Policies on the Indian Economy

The economic causes of the 1857 Revolt were deeply rooted in the exploitative policies of the British colonial administration. The economic exploitation of India by the British was multifaceted and had long-lasting effects on the Indian economy and society. The British colonial rulers implemented policies that prioritized their economic interests over the welfare of the Indian people, leading to widespread poverty, unemployment, and economic distress.

One of the most significant economic policies that contributed to the discontent was the Permanent Settlement of 1793. Under this system, the British introduced a fixed revenue system that required landowners (zamindars) to pay a fixed amount of revenue to the British government. This policy led to the exploitation of peasants, as zamindars, in their attempt to meet the revenue demands, often resorted to extortionate practices. The peasants were burdened with high taxes and were often forced to sell their produce at low prices to meet the revenue demands. This led to widespread poverty and indebtedness among the peasantry, creating a deep sense of resentment against the British.

Another significant economic policy that fueled discontent was the commercialization of agriculture. The British encouraged the cultivation of cash crops like indigo, cotton, and opium, which were in high demand in European markets. This shift in agricultural production led to a decline in the cultivation of food crops, resulting in frequent famines and food shortages. The forced cultivation of indigo, in particular, led to widespread distress among the peasants, as they were coerced into growing the crop under harsh conditions. The indigo planters, backed by the British government, exploited the peasants, leading to widespread unrest and resentment.

The British also imposed heavy tariffs on Indian goods while allowing British goods to enter India duty-free. This led to the decline of the indigenous handicraft industry, which had been a significant source of livelihood for millions of Indians. The influx of cheap British manufactured goods, especially textiles, led to the destruction of the traditional handicraft industry, leaving millions of artisans unemployed. The loss of livelihoods and the decline of traditional industries further fueled the discontent against the British.

The introduction of the Railway and Telegraph systems in India, while intended to facilitate British economic interests, also contributed to the economic discontent. The construction of railways led to the displacement of thousands of peasants from their lands, while the telegraph system was used to suppress dissent and monitor the activities of Indian leaders. The economic policies of the British, therefore, created widespread poverty, unemployment, and distress, contributing to the growing resentment against colonial rule.

Political Causes: Displacement of Traditional Power Structures

The political causes of the 1857 Revolt were closely linked to the displacement of traditional power structures by the British. The British colonial administration implemented a series of policies that undermined the authority of Indian rulers and disrupted the existing political order. The Doctrine of Lapse, introduced by Lord Dalhousie, was one of the most significant policies that contributed to the political discontent.

Under the Doctrine of Lapse, the British government claimed the right to annex any princely state where the ruler died without a male heir. This policy was used to annex several princely states, including Satara (1848), Sambalpur (1850), Jhansi (1854), and Nagpur (1853). The annexation of these states not only displaced the ruling families but also disrupted the traditional power structures, creating a sense of insecurity and resentment among the Indian rulers. The policy was seen as an aggressive expansionist measure that threatened the sovereignty of the Indian states and undermined the authority of the native rulers.

The British also implemented policies that undermined the authority of the Mughal emperor, who was seen as the symbolic head of the Indian polity. The Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was reduced to a mere figurehead with no real power or authority. The British gradually eroded the power of the Mughal court, stripping the emperor of his titles and territories. The British also moved the capital from Delhi to Calcutta, further diminishing the influence of the Mughal emperor. This policy created a deep sense of resentment among the Indian rulers, who saw the British as usurpers of their traditional authority.

The annexation of the Kingdom of Awadh in 1856 was another significant political cause of the revolt. The British justified the annexation on the grounds of misgovernance, but the real motive was to expand their territorial control in India. The annexation of Awadh led to the displacement of the Nawab and the alienation of the local population, who had been loyal to the Nawabi rule. The annexation also led to the displacement of thousands of soldiers and officials who had served the Nawab, creating a pool of disgruntled individuals who later played a significant role in the revolt.

The British also interfered in the internal affairs of the princely states, often imposing their will on the rulers. The British residents and officials stationed in the princely states often acted as de facto rulers, undermining the authority of the native princes. The interference of the British in the administration of the princely states created a sense of resentment among the rulers, who felt that their sovereignty was being eroded. The political policies of the British, therefore, created widespread discontent among the Indian rulers, who saw the British as a threat to their traditional authority and power.

Administrative Causes: Alienation Through Governance

The administrative policies of the British colonial administration were characterized by a sense of racial superiority and arrogance, which alienated the Indian population. The British officials, who were often dismissive of Indian customs and traditions, implemented policies that created a sense of alienation among the Indian masses. The judicial system, in particular, was biased in favor of the Europeans, with Indian litigants often facing discrimination and injustice in the courts.

The replacement of Persian with English as the official language of administration further alienated the Indian population. The introduction of English education, while aimed at creating a class of Western-educated Indians, also created a sense of alienation among the traditional elites, who saw their cultural and linguistic heritage being eroded. The English-educated Indians, who were initially expected to be loyal to the British, often became vocal critics of the colonial administration, leading to the rise of nationalist sentiments.

The British administration also imposed heavy taxes on the Indian population, with little regard for the welfare of the people. The land revenue system was particularly harsh, with peasants often facing extortionate demands from the British officials. The high taxes, coupled with the economic exploitation, created widespread poverty and distress among the Indian population, leading to a deep sense of resentment against the British.

The British also implemented policies that undermined the authority of traditional institutions, such as the village panchayats and local assemblies. The centralization of power in the hands of the British officials led to the erosion of local self-governance, creating a sense of alienation among the rural population. The British administration was seen as distant and unresponsive to the needs and aspirations of the Indian people, further fueling the discontent.

Social and Religious Causes: Threats to Cultural Identity

The social and religious causes of the 1857 Revolt were rooted in the perceived threat to the cultural identity of the Indian population. The British colonial administration, in its attempt to modernize and reform Indian society, introduced a series of social reforms that were seen as a threat to the traditional social order.

The Abolition of Sati (1829), which was a practice where widows were immolated on the funeral pyres of their husbands, was one of the most significant social reforms introduced by the British. While the abolition of sati was seen as a humanitarian measure by the British, it was perceived as an interference in the religious practices of the Hindus. The orthodox sections of society saw the reform as an attack on their religious beliefs and customs, leading to widespread resentment against the British.

The Widow Remarriage Act (1856), which allowed Hindu widows to remarry, was another significant social reform that created discontent among the orthodox sections of society. The reform was seen as a challenge to the traditional social norms and practices, leading to a sense of alienation among the conservative sections of society.

The activities of Christian missionaries, who were supported by the British government, also created a sense of fear and resentment among the Indian population. The missionaries were seen as agents of the British, attempting to convert the Indian population to Christianity. The fear of religious conversion was particularly strong among the Hindus and Muslims, who saw the British as a threat to their religious identity.

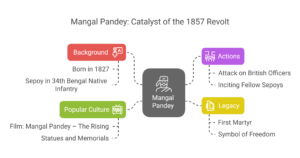

The introduction of the new Enfield rifle in the British Indian Army was the immediate trigger for the revolt. The cartridges of the rifle were rumored to be greased with the fat of cows and pigs, which offended both Hindu and Muslim soldiers. The refusal of the soldiers to use the cartridges led to widespread unrest, culminating in the mutiny at Meerut on May 10, 1857. The social and religious policies of the British, therefore, created a deep sense of resentment among the Indian population, who saw the British as a threat to their cultural and religious identity.

Military Discontent: Disaffection Among the Sepoys

The discontent among the sepoys (Indian soldiers in the British Indian Army) was a major cause of the 1857 Revolt. The sepoys, who formed the backbone of the British Indian Army, were aggrieved by a series of grievances, including low pay, lack of promotion opportunities, and the general disregard for their religious and social sensibilities.

The sepoys were paid significantly less than their British counterparts, and they were often denied promotions and other benefits. The discriminatory treatment of the sepoys created a deep sense of resentment among the Indian soldiers, who felt that their loyalty and service were not being adequately rewarded.

The introduction of the new Enfield rifle was the immediate trigger for the revolt. The cartridges of the rifle were rumored to be greased with the fat of cows and pigs, which offended both Hindu and Muslim soldiers. The refusal of the soldiers to use the cartridges led to widespread unrest, culminating in the mutiny at Meerut on May 10, 1857.

The mutiny at Meerut was the spark that ignited the larger rebellion, as the sepoys marched to Delhi, where they declared Bahadur Shah Zafar as their leader. The discontent among the sepoys was not just limited to the issue of the cartridges but was a reflection of the broader discontent among the Indian soldiers, who felt that their grievances were being ignored by the British.

The sepoys played a significant role in the revolt, as they were the first to rise against the British and were instrumental in spreading the rebellion to other parts of the country. The military discontent among the sepoys, therefore, was a major factor that contributed to the outbreak of the 1857 Revolt.

External Influences: Global Events Shaping Indian Sentiments

The early 19th century was marked by significant global events that influenced Indian sentiments and contributed to the growing discontent against British rule. The defeat of the British in the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839-42) and the Crimean War (1853-56) showcased the vulnerability of the British Empire and inspired Indian leaders and intellectuals to believe that the British could be defeated.

The rise of nationalist movements in Europe, particularly the revolutions of 1848, also influenced Indian sentiments. The ideas of nationalism, liberalism, and self-determination, which were gaining ground in Europe, inspired Indian intellectuals and leaders to challenge British colonial rule and demand greater rights and autonomy for the Indian people.

The global economic developments of the early 19th century also had an impact on India. The decline of the global demand for Indian goods, coupled with the rise of industrial capitalism in Europe, led to a decline in the traditional industries of India. The global economic changes, therefore, contributed to the economic discontent in India and fueled the resentment against British colonial rule.

The global events of the early 19th century, therefore, played a significant role in shaping Indian sentiments and contributed to the growing discontent against British colonial rule. The influence of these global events, combined with the domestic grievances, created the conditions for the outbreak of the 1857 Revolt.

The Outbreak and Expansion of the Revolt

The revolt of 1857 began as a mutiny of sepoys in the British Indian Army but quickly spread to various parts of North and Central India, drawing in large numbers of civilians and becoming a widespread rebellion against British rule. The revolt was characterized by widespread violence, with the rebels attacking symbols of British authority and declaring their loyalty to the Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar.

The Initial Trigger: The Mutiny at Meerut

The revolt began on May 10, 1857, at Meerut, where Indian sepoys, angered by the treatment of their comrades who had refused to use the greased cartridges, killed their British officers and marched to Delhi. The mutiny at Meerut was the immediate trigger for the revolt, but the underlying causes of the rebellion were much deeper, as discussed earlier.

The mutiny at Meerut was not an isolated incident but was part of a larger pattern of unrest among the sepoys. The sepoys at Meerut were aggrieved by the introduction of the new Enfield rifle and the treatment of their comrades who had refused to use the cartridges. The mutiny quickly escalated into a full-scale rebellion, as the sepoys killed their British officers and marched to Delhi, where they declared Bahadur Shah Zafar as their leader.

The mutiny at Meerut was significant because it marked the beginning of the larger rebellion against British rule. The mutiny inspired other sepoys to rise against the British, leading to the spread of the revolt to other parts of the country. The mutiny at Meerut, therefore, was the spark that ignited the larger rebellion and marked the beginning of the 1857 Revolt.

Bahadur Shah Zafar: The Symbolic Figurehead of the Revolt

The sepoys who marched to Delhi declared Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal emperor, as their leader. Although Bahadur Shah Zafar was a powerless figure, the rebels saw him as a symbol of unity against the British. His name evoked memories of the once-glorious Mughal Empire, and his leadership provided a rallying point for the disparate groups that participated in the revolt.

Bahadur Shah Zafar was initially reluctant to lead the revolt, as he was aware of the formidable power of the British. However, he eventually agreed to lead the rebels, and his leadership gave the revolt a sense of legitimacy and purpose. The rebels saw Bahadur Shah Zafar as the rightful ruler of India, and his leadership provided a unifying force for the various groups that participated in the revolt.

Bahadur Shah Zafar’s leadership, however, was more symbolic than real. The Mughal emperor was an old and frail man, with little control over the events that were unfolding around him. The real leadership of the revolt was in the hands of the sepoys and the local leaders who rose against the British. Nevertheless, Bahadur Shah Zafar’s leadership provided the revolt with a sense of unity and purpose, and his name became synonymous with the struggle against British rule.

Civilian Participation: A Widespread Insurrection

The revolt of 1857 was not just a military mutiny but a widespread civilian insurrection against British rule. The revolt quickly spread beyond the sepoys, drawing in large numbers of civilians, including peasants, artisans, and disaffected landlords. The civilian participation in the revolt was significant, as it gave the rebellion a mass character and made it a widespread insurrection against British rule.

The civilian participation in the revolt was driven by various grievances, including economic exploitation, social and religious discontent, and resentment against British policies. The peasants, who had been burdened with high taxes and forced to grow cash crops, saw the revolt as an opportunity to strike back against their oppressors. The artisans, who had been displaced by the influx of British manufactured goods, also saw the revolt as an opportunity to reclaim their livelihoods.

The disaffected landlords, who had been displaced by the British land revenue policies and the annexation of their states, also played a significant role in the revolt. The landlords saw the revolt as an opportunity to regain their lost power and influence and to challenge the authority of the British.

The civilian participation in the revolt was significant, as it gave the rebellion a mass character and made it a widespread insurrection against British rule. The revolt was no longer just a military mutiny but a popular uprising against the British, with large sections of the Indian population rising against colonial rule.

Regional Variations: Different Theaters of the Revolt

The Revolt of 1857, while often viewed as a single uprising, was a series of connected yet regionally distinct rebellions. The nature, intensity, and outcomes of the revolt varied significantly across different parts of India, influenced by local grievances, leadership, social structures, and the extent of British control. Each region had its unique dynamics that shaped the course of the rebellion.

1. Delhi: The Epicenter and Symbolic Heart of the Revolt

- The revolt in Delhi began on May 11, 1857, when sepoys from Meerut marched to the city, killing British officers and civilians, and proclaiming Bahadur Shah Zafar as the emperor of India. Delhi quickly became the nerve center of the revolt, with rebels from surrounding areas converging on the city.

- The rebellion in Delhi was characterized by its strong symbolic underpinnings. Bahadur Shah Zafar, although an elderly and reluctant leader, was seen as a unifying figurehead who could rally disparate groups against the British.

- The control of Delhi changed hands multiple times during the revolt. The city witnessed intense fighting, with the British launching a siege in July 1857. The rebels defended the city fiercely, but the British, aided by loyal Sikh and Gurkha regiments, gradually tightened their grip.

Outcome:

- Delhi fell to the British on September 20, 1857, after a brutal assault. The recapture of Delhi was a significant turning point in the revolt, both strategically and symbolically. Bahadur Shah Zafar was captured, tried, and exiled to Rangoon, marking the formal end of the Mughal dynasty.

- The city of Delhi was left in ruins, with widespread destruction and massacres of its civilian population. The suppression of the revolt in Delhi symbolized the brutal efficiency with which the British crushed the uprising.

2. Awadh (Oudh): A Region in Open Revolt

Historical Context: Awadh had been annexed by the British in 1856 under the pretext of misgovernance, a move that caused deep resentment among the local elite, particularly the taluqdars (landlords), and the deposed Nawab Wajid Ali Shah. The region was also home to a large number of sepoys who had personal and familial ties to the local population.

Nature of the Revolt:

- The revolt in Awadh was perhaps the most widespread and organized, with participation from almost all sections of society. The region’s taluqdars, who had lost their estates due to British land policies, played a crucial role in mobilizing the rural population against the British.

- The sepoys in Awadh, who had served under the Nawab and were now under British command, were among the first to revolt. They were soon joined by civilians, including peasants, artisans, and the urban poor, who were aggrieved by British economic policies.

- The revolt in Awadh was marked by widespread violence, with rebels targeting British officials, loyalists, and infrastructure. The city of Lucknow, the capital of Awadh, became a focal point of the rebellion. The siege of the British Residency in Lucknow, which lasted from June to November 1857, was one of the most dramatic episodes of the revolt.

Outcome:

- The British faced stiff resistance in Awadh, but with the help of reinforcements and loyalist forces, they were able to gradually suppress the rebellion. Lucknow was recaptured in March 1858 after a protracted siege.

- The suppression of the revolt in Awadh was marked by brutal reprisals. Entire villages were destroyed, and thousands of rebels and civilians were killed. The region was left devastated, and British policies were reasserted with even greater harshness.

- The fall of Awadh marked the end of major organized resistance in the North, though guerrilla warfare continued for some time.

3. Central India: The Fierce Resistance of Rani Lakshmibai and Tatya Tope

Historical Context: Central India, particularly the region around Jhansi, Gwalior, and Kanpur, was a significant theater of the revolt. The region was home to several princely states that had been brought under British control through the Doctrine of Lapse, which allowed the British to annex any princely state where the ruler died without a direct male heir.

Key Figures:

- Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi: The young queen of Jhansi, Rani Lakshmibai, became one of the most iconic figures of the revolt. After the British refused to recognize her adopted son as the heir to the throne, she led her forces in a fierce rebellion against the British.

- Tatya Tope: A close associate of Nana Saheb, the deposed Peshwa of the Marathas, Tatya Tope was a brilliant military strategist who played a key role in organizing rebel forces in Central India.

Nature of the Revolt:

- The revolt in Central India was characterized by its strong leadership and intense military engagements. Rani Lakshmibai, known for her valor, personally led her troops in battle, defending Jhansi against British forces. The siege of Jhansi in March 1858 was a significant event, with Rani Lakshmibai resisting the British assault with determination.

- Tatya Tope conducted a series of successful guerrilla campaigns against the British, often outmaneuvering them in battles across Central India. He attempted to rally various regional forces and led them in several successful engagements, including the capture of Gwalior, which temporarily became a rebel stronghold.

- The rebellion in Central India was marked by several key battles, including the battles of Kalpi, Gwalior, and Jhansi. The rebels managed to capture several British forts and towns, creating a formidable resistance against British efforts to regain control.

Outcome:

- Despite initial successes, the British, with their superior numbers and resources, gradually recaptured most of Central India. Jhansi fell in April 1858 after a fierce battle in which Rani Lakshmibai was killed. Her death marked the end of major resistance in Jhansi.

- Tatya Tope continued to lead guerrilla warfare for some time, but the British eventually captured and executed him in April 1859. The fall of Gwalior in June 1858 marked the collapse of organized resistance in Central India.

- The suppression of the revolt in Central India was followed by widespread retribution, with the British brutally punishing those involved in the rebellion.

- The revolt in Bihar was largely driven by local grievances, particularly those related to British land revenue policies that had adversely affected zamindars and peasants alike. Kunwar Singh, despite his advanced age, took up arms against the British and quickly became a rallying figure for the rebellion in Bihar.

- Kunwar Singh’s rebellion was characterized by a series of guerrilla campaigns against the British. He managed to elude capture multiple times and inflicted significant damage on British forces, using his deep knowledge of the local terrain to his advantage.

- The rebellion in Bihar saw active participation from local zamindars and peasants, who supported Kunwar Singh in his efforts to resist British authority. His forces engaged in several battles, including the Battle of Arrah, where they inflicted a notable defeat on the British.

- The British, recognizing the threat posed by Kunwar Singh, launched a concerted campaign to capture him. Despite his resilience, the rebellion in Bihar was gradually suppressed by mid-1858.

- Kunwar Singh continued to fight even after being mortally wounded, eventually dying from his injuries in April 1858. His death marked the end of the major rebellion in Bihar, though smaller skirmishes continued for some time.

- The suppression of the revolt in Bihar was followed by harsh reprisals, with the British punishing those who had supported the rebellion and reasserting control over the region.

5. Bengal: Limited Resistance

Historical Context: Bengal, under British control since the Battle of Plassey in 1757, was one of the earliest regions to come under colonial rule. By 1857, Bengal had a well-established British administration, and the local elite had largely adapted to British rule, making the region relatively stable compared to other parts of India.

Nature of the Revolt:

- The revolt in Bengal was relatively subdued, with only isolated incidents of rebellion. The region’s long history of British rule had led to the entrenchment of colonial administration and the co-optation of the local elite, reducing the likelihood of widespread rebellion.

- Some isolated incidents of resistance occurred in Bengal, particularly among the sepoys stationed there, but these were quickly contained by the British. The lack of significant leadership and coordination in Bengal meant that the revolt never gained the same momentum as it did in regions like Awadh or Central India.

- The British were able to maintain control in Bengal through a combination of military force and the support of local loyalists, who had benefited from British rule and were unwilling to jeopardize their position.

Outcome:

- The British swiftly suppressed any signs of rebellion in Bengal, ensuring that the region remained relatively calm throughout the period of the revolt.

- The limited nature of the revolt in Bengal meant that the region did not experience the same level of violence or disruption as other parts of India, allowing the British to focus their resources on suppressing the rebellion elsewhere.

6. Maharashtra: Scattered and Limited Resistance

Historical Context: Maharashtra, the heartland of the Maratha Empire, had a complex history of resistance against British rule. However, by 1857, the British had successfully subdued the Maratha confederacy and integrated the region into their colonial administration. The region had a mix of loyalist princely states and areas directly administered by the British.

- The revolt in Maharashtra was limited and scattered, with only a few isolated incidents of resistance. The region’s princely states, such as the Kingdom of Satara, had already been annexed by the British, and the local elite had largely been co-opted into the colonial administration.

- Some minor uprisings occurred, particularly among discontented sepoys and local chieftains, but these were not coordinated and lacked the leadership necessary to pose a significant challenge to British rule.

- The British were able to quickly suppress these isolated incidents, using a combination of military force and the support of local loyalists who had benefited from British rule.

Outcome:

- The British maintained control over Maharashtra throughout the revolt, with minimal disruption to their administration. The region’s limited participation in the revolt meant that it did not experience the same level of violence or upheaval as other parts of India.

- The scattered nature of the rebellion in Maharashtra reflected the broader regional variations in the revolt, with some areas remaining relatively calm while others were engulfed in intense conflict.

The Suppression of the Revolt: British Response

The British response to the revolt was swift and brutal. The British authorities, caught off guard by the scale of the rebellion, initially struggled to contain the revolt. However, by late 1857, the British had regained control of most of the rebel-held territories and began a campaign of repression to crush the rebellion.

Reinforcements from Britain: The Arrival of British Troops

The British response to the revolt was initially hampered by the lack of troops and resources. The British Indian Army was stretched thin, with many of its units engaged in other parts of the empire. However, the British government quickly dispatched reinforcements from Britain to quell the rebellion.

The arrival of British troops was a turning point in the suppression of the revolt. The British troops, well-trained and well-equipped, were able to defeat the rebel forces in a series of battles and recapture the rebel-held territories. The British also employed the use of heavy artillery and modern weapons, which gave them a significant advantage over the poorly armed rebels.

The British troops were also supported by loyalist forces, including the Sikh regiments and the Gurkhas, who played a significant role in suppressing the revolt. The loyalist forces were instrumental in recapturing the rebel-held territories and defeating the rebel leaders.

The arrival of British troops, therefore, marked a turning point in the suppression of the revolt. The British, with their superior firepower and resources, were able to defeat the rebel forces and recapture the rebel-held territories.

The Recapture of Delhi: The Fall of the Mughal Capital

The recapture of Delhi was one of the most significant events in the suppression of the revolt. Delhi, which had been declared the capital of the rebel government, was a symbol of the rebellion and its recapture was seen as a major victory for the British.

The British launched a major offensive to recapture Delhi in September 1857. The battle for Delhi was intense, with the British facing stiff resistance from the rebel forces. However, the British were able to breach the city’s defenses and capture the city after several days of heavy fighting.

The fall of Delhi marked the end of the Mughal Empire, as Bahadur Shah Zafar was captured by the British and later exiled to Rangoon. The recapture of Delhi was a major blow to the rebellion, as it deprived the rebels of their symbolic leader and capital.

The British, however, faced continued resistance in other parts of the country, particularly in Awadh and Central India. The British, therefore, launched a series of campaigns to recapture the rebel-held territories and suppress the remaining rebel forces.

The Siege of Lucknow: The Long Battle for Awadh

The siege of Lucknow was one of the most significant battles of the revolt. Lucknow, the capital of Awadh, had been captured by the rebel forces, who declared the deposed Nawab, Wajid Ali Shah, as their leader. The British, determined to recapture the city, launched a major offensive to break the siege.

The siege of Lucknow was marked by intense fighting, with the British facing stiff resistance from the rebel forces. The British, however, were able to break the siege after several months of heavy fighting and recapture the city in March 1858.

The recapture of Lucknow marked the end of the rebellion in Awadh, as the rebel forces were defeated and their leaders captured or killed. The British, however, faced continued resistance in Central India, where the revolt was led by Rani Lakshmibai and Tatya Tope.

The siege of Lucknow, therefore, was a significant event in the suppression of the revolt, as it marked the defeat of the rebels in one of the most important theaters of the rebellion.

The Fall of Jhansi: Rani Lakshmibai’s Heroic Resistance

The revolt in Central India was led by Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi, who became one of the most iconic figures of the rebellion. Rani Lakshmibai, who had been denied the right to adopt an heir after the death of her husband, led the revolt against the British in Jhansi and became a symbol of resistance against colonial rule.

The British, determined to recapture Jhansi, launched a major offensive against the city in early 1858. The battle for Jhansi was intense, with Rani Lakshmibai leading her forces in a heroic defense of the city. However, the British, with their superior firepower and resources, were able to breach the city’s defenses and capture Jhansi in April 1858.

Rani Lakshmibai, who refused to surrender, was killed in battle, becoming a martyr for the cause of Indian independence. The fall of Jhansi marked the end of the rebellion in Central India, as the rebel forces were defeated and their leaders captured or killed.

The British, however, faced continued resistance from Tatya Tope, who continued to lead the rebellion in other parts of Central India. The British, therefore, launched a series of campaigns to suppress the remaining rebel forces and recapture the rebel-held territories.

The Capture of Tatya Tope: The End of the Armed Resistance

The capture of Tatya Tope marked the end of the armed resistance against British rule. Tatya Tope, one of the most prominent leaders of the revolt, had led the rebellion in Central India and continued to resist the British even after the fall of Jhansi.

The British, determined to capture Tatya Tope, launched a series of campaigns to track him down. Tatya Tope, who had been on the run for several months, was eventually betrayed by one of his own followers and captured by the British in April 1859.

Tatya Tope was tried and executed by the British, marking the end of the armed resistance against colonial rule. The capture and execution of Tatya Tope was a major blow to the rebellion, as it deprived the rebels of one of their most capable leaders.

The British, however, faced continued resistance in some parts of the country, particularly in rural areas where the rebellion had taken on the character of a peasant uprising. The British, therefore, continued to use repression and force to suppress the remaining pockets of resistance and restore order.

Reasons for the Failure of the Revolt of 1857

The Revolt of 1857, despite its intensity and widespread nature, ultimately failed to achieve its objective of overthrowing British rule in India. The reasons for the failure of the revolt were multifaceted and rooted in various socio-political, economic, and military factors. Understanding these reasons is crucial for comprehending why this significant uprising could not sustain itself or spread uniformly across the Indian subcontinent.

Limited Geographical Spread: Lack of All-India Participation

One of the primary reasons for the failure of the revolt was the absence of all-India participation. The revolt was largely confined to the northern and central parts of India, with major centers in Delhi, Awadh, Bihar, and Central India. Key regions such as Bengal, Bombay, Madras, Punjab, and the southern princely states remained largely unaffected by the uprising. This geographical limitation significantly reduced the impact and reach of the revolt, preventing it from becoming a pan-Indian movement.

In many parts of India, the British had strong support from local rulers and elites who saw the British as allies rather than oppressors. For example, the princely states of Punjab and the southern regions either remained loyal to the British or chose not to participate actively in the revolt. This lack of unity across different regions of India hindered the possibility of a coordinated and widespread rebellion that could have posed a more formidable challenge to British rule.

Fragmented Social Support: Non-Participation of All Classes

Another significant factor contributing to the failure of the revolt was the lack of participation from all social classes. While the revolt saw the active involvement of peasants, artisans, sepoys, and disaffected landlords, it did not receive the support of key sections of Indian society, particularly the educated middle class, merchants, and the newly emerging Western-educated elite.

The merchants and traders, who were often beneficiaries of British economic policies, were hesitant to support a movement that could disrupt their commercial interests. Similarly, the Western-educated Indians, who were beginning to benefit from the new educational and employment opportunities under British rule, were not inclined to join a revolt that seemed to lack a clear vision for the future of India. This absence of widespread social support weakened the revolt’s momentum and prevented it from becoming a unified national movement.

Inferior Weaponry and Equipment: Disadvantage in Arms

The revolt of 1857 also failed due to the inferior arms and equipment used by the rebels compared to the British forces. The British army was equipped with modern weapons, including Enfield rifles and heavy artillery, while the Indian rebels largely relied on outdated weaponry, swords, spears, and locally made firearms.

This disparity in military technology was a significant disadvantage for the rebels, as they were unable to match the firepower and strategic capabilities of the British forces. The lack of access to modern weapons, coupled with inadequate training and resources, made it difficult for the rebels to sustain their fight against the well-equipped and professionally trained British troops.

Poor Coordination and Organization: Lack of Centralized Leadership

The revolt suffered from poor coordination and organization, which further contributed to its failure. The uprising was marked by a lack of centralized leadership, with different leaders and factions operating independently in various regions. While figures like Bahadur Shah Zafar, Nana Sahib, Rani Lakshmibai, and Tatya Tope emerged as leaders in their respective regions, there was no overarching strategy or unified command to coordinate the efforts of the rebels across India.

This lack of coordination led to disjointed and uncoordinated attacks, allowing the British to isolate and suppress individual centers of rebellion one by one. The absence of a unified leadership also made it difficult for the rebels to sustain their efforts over a prolonged period, as they were unable to consolidate their gains or mount a cohesive resistance against the British.

Absence of a Unified Ideology: No Common Cause

The revolt of 1857 also lacked a unified ideology or common cause that could have united the diverse groups participating in the rebellion. The uprising was driven by a range of grievances, including economic exploitation, political discontent, religious concerns, and military grievances. However, these grievances were often localized and specific to particular regions or groups, rather than being part of a broader nationalistic or ideological movement.

The absence of a common ideological framework meant that the different groups involved in the revolt were not united by a shared vision for the future of India. This lack of unity made it difficult for the rebels to sustain their efforts or rally widespread support for their cause. The British, on the other hand, were able to exploit these divisions and play different groups against each other, further weakening the revolt.

The Hindu-Muslim Unity Factor: A Missed Opportunity

The Revolt of 1857 is often cited as an example of Hindu-Muslim unity in the struggle against British rule. In many regions, Hindus and Muslims fought side by side against the British, with leaders from both communities playing prominent roles in the rebellion. However, this unity was not universal or sustained, and the potential for a broader Hindu-Muslim alliance was ultimately undermined by various factors.

Early Signs of Unity: Joint Efforts in the Rebellion

In the initial stages of the revolt, there were several instances of Hindu-Muslim unity, with both communities coming together to fight against the British. For example, the decision to reinstate Bahadur Shah Zafar as the symbolic leader of the revolt was supported by both Hindu and Muslim leaders, who saw the Mughal emperor as a unifying figure.

Similarly, in regions like Awadh and Central India, Hindu and Muslim leaders worked together to organize and lead the rebellion. The participation of figures like Nana Sahib, Rani Lakshmibai, and Tatya Tope alongside Muslim leaders like Maulvi Ahmadullah Shah highlighted the potential for a united front against British rule.

Missed Opportunities: Lack of Sustained Unity

Despite these early signs of unity, the revolt ultimately failed to sustain a broader Hindu-Muslim alliance. The British were able to exploit existing religious and social divisions to weaken the rebellion and prevent the formation of a unified front. In some regions, the British actively encouraged divisions between Hindus and Muslims, using policies of divide and rule to undermine the unity of the rebels.

The lack of a shared ideological framework also contributed to the erosion of Hindu-Muslim unity. While both communities shared grievances against British rule, their motivations and objectives were not always aligned. The absence of a common cause or vision for the future of India made it difficult to maintain the initial unity that had characterized the early stages of the revolt.

The Nature of the Revolt: A Complex Uprising

The nature of the Revolt of 1857 has been the subject of much debate among historians, with different interpretations offered about its character and significance. The uprising has been variously described as a mutiny, a rebellion, a war of independence, and a popular insurrection. Understanding the complex nature of the revolt is crucial for appreciating its impact on Indian history.

A Military Mutiny: The Sepoy Rebellion

At its core, the Revolt of 1857 began as a military mutiny, with sepoys in the British Indian Army rising against their officers. The immediate trigger for the revolt was the introduction of the new Enfield rifle, which was rumored to require cartridges greased with cow and pig fat, offensive to both Hindu and Muslim soldiers. The sepoys’ grievances, however, went beyond this single issue and included a range of economic, social, and political concerns.

The revolt quickly spread from the military to the civilian population, drawing in large numbers of peasants, artisans, and disaffected landlords. While the military dimension of the revolt was significant, the uprising soon took on the character of a broader rebellion against British rule, with civilians joining the fight in large numbers.

A Popular Uprising: Civilian Participation

The Revolt of 1857 was not just a military mutiny but also a popular uprising, with large sections of the Indian population rising against British rule. The rebellion saw the active participation of peasants, artisans, and landlords, who had their own grievances against the British administration. The economic exploitation, heavy taxation, and social and religious interference by the British fueled the anger of the Indian population, leading to widespread support for the revolt.

The popular character of the uprising gave it a mass appeal and made it more than just a military rebellion. The revolt became a widespread insurrection against British rule, with civilians in many regions taking up arms and joining the fight against the colonial authorities.

A War of Independence? The Nationalist Interpretation

In the years following the revolt, Indian nationalists came to view the uprising as the first war of Indian independence. This interpretation emphasizes the revolt’s significance as a challenge to British colonial rule and its role as a precursor to the later nationalist movement.

The nationalist interpretation of the revolt sees it as a heroic struggle for freedom, with leaders like Rani Lakshmibai, Tatya Tope, and Bahadur Shah Zafar becoming symbols of resistance against colonial oppression. While the revolt ultimately failed to achieve its objective, it is seen as laying the foundation for the later struggle for independence, inspiring future generations of Indian leaders and freedom fighters.

The Aftermath and Consequences of the Revolt

The revolt of 1857 had far-reaching consequences for both India and Britain. Although the rebellion was ultimately unsuccessful in overthrowing British rule, it marked a turning point in the history of India and had a profound impact on the future course of the Indian independence movement.

The End of the Mughal Empire: The Exile of Bahadur Shah Zafar

The revolt of 1857 marked the end of the Mughal Empire, which had been in decline for several decades. The British, after recapturing Delhi, exiled Bahadur Shah Zafar to Rangoon, where he lived out the rest of his life in obscurity. The exile of Bahadur Shah Zafar marked the formal end of the Mughal Empire, which had been a dominant force in Indian history for several centuries.

The British, after the suppression of the revolt, formally abolished the Mughal Empire and declared India to be a crown colony, directly under the control of the British government. The abolition of the Mughal Empire marked the end of a significant chapter in Indian history and the beginning of a new era of direct British rule.

The Transfer of Power: The End of Company Rule

The revolt of 1857 led to the end of the rule of the East India Company, which had been the dominant power in India for over a century. The British government, in the aftermath of the revolt, decided to abolish the East India Company and transfer the control of India directly to the British Crown.

The Government of India Act of 1858 marked the formal transfer of power from the East India Company to the British Crown. The Act created the office of the Secretary of State for India, who was responsible for the administration of India, and established the Indian Civil Service to oversee the governance of the country.

The transfer of power marked the beginning of a new era of British rule in India, with the British government taking direct control of the administration of the country. The British, in the aftermath of the revolt, also implemented a series of reforms to consolidate their control over India and prevent future rebellions.

Reorganization of the Army: The Reassertion of British Control

The revolt of 1857 led to a major reorganization of the British Indian Army. The British, in the aftermath of the revolt, sought to prevent future rebellions by reorganizing the army and reducing the proportion of Indian soldiers in the military.

The British also implemented a series of measures to ensure the loyalty of the Indian soldiers, including the recruitment of soldiers from different regions and communities to prevent the formation of a united front against British rule. The British also increased the proportion of European soldiers in the army and reduced the reliance on Indian soldiers.

The reorganization of the army was a significant step in the reassertion of British control over India. The British, through the reorganization of the army, sought to prevent future rebellions and ensure the loyalty of the Indian soldiers.

Economic and Social Impact: The Consolidation of British Rule

The revolt of 1857 had a significant impact on the Indian economy and society. The British, in the aftermath of the revolt, implemented a series of economic and social reforms to consolidate their control over India and prevent future rebellions.

The British implemented a series of land revenue reforms, including the introduction of the Ryotwari system in Madras and Bombay and the Mahalwari system in North India, to increase revenue collection and ensure the loyalty of the landlords. The British also introduced a series of social reforms, including the promotion of Western education and the spread of Christianity, to weaken the influence of traditional institutions and ensure the loyalty of the Indian population.

The economic and social impact of the revolt was significant, as it led to the consolidation of British rule in India and the creation of a new social and economic order. The British, through their reforms, sought to create a loyal and obedient population that would not challenge their authority in the future.

The Rise of Nationalism: The Legacy of the Revolt

The revolt of 1857, although unsuccessful in overthrowing British rule, left a lasting legacy that contributed to the rise of Indian nationalism. The rebellion, which was the first widespread challenge to British rule, inspired future generations of Indian leaders and freedom fighters to continue the struggle for independence.

The revolt of 1857 also led to a reassessment of British policies in India, with the British government implementing a series of reforms to address the grievances of the Indian population. The British, however, continued to face resistance from the Indian population, leading to the emergence of the Indian National Congress in 1885 and the beginning of the organized nationalist movement.

The legacy of the revolt of 1857 was significant, as it marked the beginning of the Indian struggle for independence and inspired future generations of Indians to challenge British rule. The revolt, therefore, was a turning point in the history of India and laid the foundation for the future independence movement.

SHORT NOTES

Underlying Causes:

• Economic Exploitation:

- Permanent Settlement (1793): Forced zamindars to extract high revenues from peasants, leading to poverty and indebtedness.

- Commercialisation of Agriculture: Focus on cash crops (indigo, cotton, opium) led to food shortages and famines.

- De-industrialisation: British policies destroyed India’s traditional handicraft industries, causing unemployment.

• Political Discontent:

- Doctrine of Lapse: Used by Lord Dalhousie to annexe princely states (Satara, Jhansi, Nagpur, etc.) when rulers died without male heirs. This angered the ruling families and created fear among other rulers.

- Erosion of Mughal Authority: The Mughal emperor was reduced to a mere figurehead, further fueling resentment against the British.

• Administrative Alienation:

- Racist and Biased Administration: British officials often displayed arrogance and disregard for Indian customs and traditions.

- Imposition of English: Replacing Persian as the official language alienated many Indians.

- Judicial System: Favored Europeans over Indians.

• Socio-Religious Concerns:

- Social Reforms: British reforms like the abolition of Sati and the Widow Remarriage Act were seen as attacks on Indian traditions.

- Missionary Activities: Christian missionaries, often supported by the British, were perceived as a threat to Hinduism and Islam.

- Enfield Rifle Controversy: The greased cartridges issue became the immediate trigger for the revolt, as it offended both Hindu and Muslim religious sentiments.

• Military Grievances:

- Discrimination: Indian sepoys received lower pay and fewer promotion opportunities compared to their British counterparts.

- Disregard for Religious Beliefs: The Enfield rifle controversy highlighted the British insensitivity towards the sepoys’ religious beliefs.

• Key Events and Regional Variations:

- May 10, 1857: Mutiny erupts at Meerut. Sepoys kill British officers and march to Delhi.

- Delhi: Sepoys proclaim Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal emperor, as the leader of the revolt. Delhi becomes a major center of the rebellion.

- Awadh (Oudh): Annexed by the British in 1856, Awadh witnessed widespread revolt led by dispossessed landlords (taluqdars) and sepoys. The siege of Lucknow was a key event.

- Central India: Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi and Tatya Tope emerged as prominent leaders, fiercely resisting the British. The fall of Jhansi and the capture of Gwalior were significant events.

- Bihar: Kunwar Singh, an elderly zamindar, led a guerrilla campaign against the British.

- Other Regions: While the revolt was concentrated in North and Central India, there were sporadic uprisings in other areas. However, regions like Bengal and Maharashtra remained relatively calm.

• Suppression of the Revolt:

- British Reinforcements: The arrival of troops from Britain proved crucial in suppressing the revolt.

- Superior Firepower: The British had modern weapons and artillery, giving them a significant advantage over the rebels.

- Loyalist Support: The British also relied on support from Sikh and Gurkha regiments.

- Key Battles and Events:

- Recapture of Delhi (September 1857).

- Relief of Lucknow (November 1857) and its final recapture (March 1858).

- Fall of Jhansi (April 1858) and death of Rani Lakshmibai.

- Capture and execution of Tatya Tope (April 1859).

Reasons for Failure:

- Limited Geographical Spread: The revolt was largely confined to North and Central India, lacking a pan-Indian character.

- Lack of Unity: Not all social classes and communities actively participated in the revolt. The educated middle class and merchants largely remained aloof.

- Inferior Weaponry: The rebels were poorly equipped compared to the British.

- Lack of Coordination: The revolt lacked a centralized leadership and a unified strategy.

- Missed Opportunities: The potential for a strong Hindu-Muslim alliance was not fully realized.

- British Strength: The British had superior military resources, organization, and the support of loyalist forces.

Nature of the Revolt:

- Military Mutiny: It began as a mutiny of sepoys against their British officers.

- Popular Uprising: It evolved into a widespread rebellion with significant civilian participation.

- First War of Independence: Nationalist historians view it as the first major struggle for Indian independence.

Consequences:

- End of the Mughal Empire: Bahadur Shah Zafar was exiled, marking the formal end of the Mughal dynasty.

- End of Company Rule: The British government abolished the East India Company and took direct control of India.

- Army Reorganization: The British reorganized the army to prevent future revolts, reducing the proportion of Indian soldiers and ensuring greater control.

- Social and Economic Impact: The British implemented policies to consolidate their rule and further their economic interests.

- Rise of Nationalism: The revolt played a crucial role in fostering Indian nationalism and inspiring the later struggle for independence.

COSMOS XTRA+

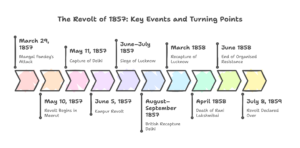

Timeline of the Revolt of 1857

Early Developments and Rising Tensions

- 1793: Permanent Settlement introduced, leading to peasant exploitation.

- 1829: Abolition of Sati.

- 1839-42: First Anglo-Afghan War (British defeat).

- 1848: Annexation of Satara under the Doctrine of Lapse.

- 1850: Annexation of Sambalpur.

- 1853: Annexation of Nagpur.

- 1853-56: Crimean War (British vulnerability exposed).

- 1854: Annexation of Jhansi.

- 1856:

- Annexation of Awadh.

- Widow Remarriage Act passed.

Outbreak and Spread of the Revolt

- March 29, 1857: Mangal Pandey protests against the new Enfield rifle cartridges at Barrackpore.

- May 10, 1857: Mutiny at Meerut. Sepoys rise up and march to Delhi.

- May 11, 1857: Rebels reach Delhi and proclaim Bahadur Shah Zafar as their leader.

- May – June 1857: Revolt spreads to various parts of North and Central India, including Kanpur, Lucknow, Jhansi, and Gwalior.

Key Battles and Events

- June 1857: Siege of Lucknow begins.

- September 1857: British recapture Delhi. Bahadur Shah Zafar is captured and exiled.

- March 1858: British recapture Lucknow.

- April 1858: Fall of Jhansi. Rani Lakshmibai is killed in battle.

- June 1858: British recapture Gwalior.

- April 1859: Tatya Tope is captured and executed.

Aftermath and Long-Term Impact

- 1858: Government of India Act passed, transferring power from the East India Company to the British Crown.

- Post-1858: British implement policies to consolidate their rule and prevent future uprisings.

- Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries: The Revolt of 1857 inspires the growth of Indian nationalism and the struggle for independence.

This timeline provides a chronological overview of the major events leading up to, during, and after the Revolt of 1857. It should help you understand the sequence of events and their significance in the broader context of the revolt.

PRACTICE QUES

1. Which of the following statements regarding the Enfield rifle cartridge controversy is correct?

- The cartridge was greased with cow and pig fat.

- Soldiers had to bite the cartridge open with their teeth.

- British officers confirmed the presence of animal fat.

Explanation: One of the major immediate causes of the revolt was the introduction of the Enfield rifle. The cartridges for this rifle were greased with animal fat, specifically from cows and pigs—offensive to both Hindus and Muslims. Soldiers had to bite the cartridges open, and this act was seen as a direct threat to their religion. Although the British denied it, the belief spread rapidly among the sepoys and caused mass resentment, ultimately acting as the spark for the uprising.

Correct Answer: A

2. Which of the following was a political cause of the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: The British expansionist policies, especially under Lord Dalhousie, alienated Indian rulers. The Doctrine of Lapse allowed the British to annex any princely state without a male heir. Under the Subsidiary Alliance system, Indian states lost their sovereignty. The symbolic removal of Mughal power, like denying Bahadur Shah Zafar the right to be called emperor, deeply offended Indian sentiment. These moves collectively fostered a climate of political unrest.

Correct Answer: D

3. With reference to the Revolt of 1857, which of the following pairs is correctly matched?

- Awadh — Begum Hazrat Mahal

- Jhansi — Kunwar Singh

- Kanpur — Bahadur Shah Zafar

Explanation: Begum Hazrat Mahal took charge of the revolt in Awadh after the annexation of the region. Jhansi was led by Rani Lakshmibai, not Kunwar Singh—he led the revolt in Bihar. Kanpur was under the leadership of Nana Saheb and Tantia Tope, while Bahadur Shah Zafar was declared the symbolic leader of the revolt in Delhi. Understanding the correct leaders helps in mapping the geographic spread and intensity of the revolt.

Correct Answer: A

4. Which of the following were social-religious causes of the Revolt of 1857?

- Abolition of Sati

- Legalization of widow remarriage

- Conversion of Indians to Christianity

- Suppression of traditional customs

Explanation: Many Indians saw the social reforms introduced by the British as intrusive and disrespectful to traditional beliefs. Though practices like Sati were regressive, their abolition and the legalization of widow remarriage were seen by conservatives as British attempts to interfere in Indian culture. Moreover, the spread of Christian missionaries and conversions added to fears that the British intended to impose Christianity, leading to a strong cultural backlash.

Correct Answer: D

5. Who among the following was the leader of the rebellion in Jhansi during the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi was one of the most prominent and fearless leaders of the 1857 revolt. She led her troops with valor and resilience, famously defending the city of Jhansi against the British forces. After the fall of Jhansi, she continued to fight for the cause of independence and became an iconic figure in Indian history, symbolizing courage and resistance.

Correct Answer: A

6. Which of the following actions by the British government angered the sepoys and led to the rebellion?

- Introduction of the Enfield rifle

- Annexation of Indian territories

- Outlawing of traditional practices

- Imposition of heavy taxes

Explanation: The British actions—such as the introduction of the Enfield rifle, which required sepoys to bite a cartridge greased with animal fat, and the annexation of several Indian states under the Doctrine of Lapse—angered many Indians. Additionally, the British government's interference in traditional practices, such as outlawing Sati and introducing social reforms, created resentment. This widespread dissatisfaction culminated in the 1857 uprising. While heavy taxes were also a cause of discontent, the initial trigger and the listed items 1, 2, and 3 were very direct causes of the rebellion.

Correct Answer: B

7. Which of the following territories did NOT witness major revolts during the 1857 uprising?

Explanation: While regions like Delhi, Kanpur, and Lucknow saw significant uprisings during the 1857 Revolt, the southern parts of India, including Madras (present-day Chennai), did not actively participate. The revolt was mainly centered in North and Central India, where widespread resistance against British rule occurred, led by local rulers and military personnel.

Correct Answer: C

8. Which of the following was the last stronghold of the Indian rebels during the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: Delhi was the last major stronghold of the Indian rebels during the 1857 Revolt. The city had been declared the center of the rebellion with Bahadur Shah Zafar as its symbolic leader. The British forces laid siege to Delhi for several months before finally capturing it in September 1857, marking a significant turning point and effectively the fall of the organized rebellion.

Correct Answer: C

9. Who was the British commander who played a major role in suppressing the revolt in Kanpur?

Explanation: Sir Colin Campbell, along with Sir Henry Havelock, played a key role in recapturing Kanpur from the rebel forces. After the fall of the city to Nana Saheb’s forces, Campbell led the British army in a series of battles that ultimately restored British control over the region. His role in suppressing the revolt earned him recognition, but also controversy due to the brutal repression of the rebels.

Correct Answer: B

10. The last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was exiled to which location after the suppression of the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: Bahadur Shah Zafar, after the suppression of the 1857 Revolt, was captured by the British. The British, aiming to remove him as a figurehead for further uprisings, exiled him to Rangoon (present-day Yangon) in Burma (Myanmar). His exile marked the effective end of the Mughal Empire and the beginning of direct British rule in India.

Correct Answer: C

11. The Revolt of 1857 is also known as which of the following in Indian history?

Explanation: The Revolt of 1857 is known by several names. In India, it is often referred to as the 'First War of Independence,' recognizing it as the first significant attempt by Indians to challenge British colonial rule. The British called it the 'Sepoy Rebellion,' due to the primary role of Indian soldiers (sepoys) in the military. It is also referred to as a 'mutiny' by some historians, particularly British, who viewed it as a rebellion confined to the military ranks rather than a widespread national uprising.

Correct Answer: D

12. Which of the following was the immediate cause of the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: The introduction of the Enfield rifle and its controversial greased cartridges was the immediate trigger for the Revolt of 1857. This sparked widespread anger among the sepoys, as they had to bite open the cartridges, which were allegedly made of cow and pig fat. This deeply offended both Hindu and Muslim soldiers, leading to a large-scale uprising against British rule. While the other options were underlying causes, the cartridge issue was the spark.

Correct Answer: A

13. Which of the following leaders of the Revolt of 1857 is known for his leadership in Bihar?

Explanation: Kunwar Singh was a prominent leader in Bihar during the 1857 revolt. A Rajput ruler, he led a determined resistance against British forces in Bihar and neighboring regions. Despite his age and limited resources, he showed remarkable courage and strategic acumen in battles. He is considered one of the major leaders of the revolt in Eastern India.

Correct Answer: B

14. Which city witnessed a brutal massacre of Indian rebels after their surrender during the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: After the fall of Kanpur, the British forces under Sir Colin Campbell were involved in brutal actions against Indian rebels and civilians. This incident, sometimes referred to as the 'Cawnpore massacre' (though the term typically refers to the killing of British women and children by rebels), highlights the extreme violence that occurred in the city. The subsequent British reprisal was also harsh. While the question phrasing is ambiguous about *which* massacre, Kanpur was indeed a site of extreme violence involving both sides. The British forces' actions after re-taking the city were particularly harsh.

Correct Answer: B

15. Who among the following was not associated with the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India, was not associated with the Revolt of 1857. He was born in 1889, long after the events of 1857. On the other hand, Mangal Pandey was one of the first to rise against the British at the Barrackpore cantonment, and Tantiya Tope was a key military leader in the revolt. Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal emperor, played a symbolic role as the figurehead of the rebellion.

Correct Answer: D

16. What was the role of women in the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: Women played a significant and diverse role in the Revolt of 1857. Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi and Begum Hazrat Mahal of Awadh are prime examples of women who not only participated but also bravely led the rebellion in their respective regions. Beyond direct leadership, women also provided crucial logistical support, covert assistance, and inspired resistance.

Correct Answer: C

17. Which of the following was a consequence of the Revolt of 1857?

Explanation: While the Revolt of 1857 did not immediately end British rule, it led to a significant shift in governance. The British East India Company's rule was abolished, and the direct administration of India was taken over by the British Crown through the Government of India Act, 1858. This marked the beginning of the British Raj and major administrative changes.

Correct Answer: B

18. Which of the following was NOT a key reason for the British to suppress the Revolt of 1857 so ruthlessly?

Explanation: The British ruthlessly suppressed the revolt primarily to re-establish their authority, deter future uprisings (by setting a harsh example), and punish those involved. Increasing British support among Indian rulers was an outcome of their *subsequent* policy (e.g., policy of 'paramountcy' and non-annexation) rather than a direct reason for the initial ruthless suppression, which actually alienated many. The suppression itself was more about force and control than about winning hearts and minds at that moment.

Correct Answer: D

19. The British strategy of dividing and ruling during the Revolt of 1857 mainly involved:

Explanation: The British successfully used the "divide and rule" policy by exploiting existing divisions and creating new ones. During the Revolt, they forged alliances with certain Indian rulers (like the Nizam of Hyderabad, the Sikhs, and the Gurkhas) who remained loyal or actively supported the British, using their forces and resources to suppress the rebellion. This was a crucial factor in the British victory.

Correct Answer: A

20. Who was the British officer responsible for the suppression of the Revolt of 1857 in Delhi?

Explanation: John Nicholson played a critical and decisive role in the suppression of the Revolt of 1857 in Delhi. He commanded the British forces during the siege and recapture of Delhi, though he was mortally wounded during the final assault. His military leadership and aggressive tactics were crucial in breaking the rebel resistance in the city.

Correct Answer: C

Discuss the immediate and underlying causes of the Revolt of 1857.

Evaluate the role of Indian sepoys in the initiation and spread of the Revolt of 1857.

To what extent can the Revolt of 1857 be called a national movement? Substantiate your answer.

Analyze the role played by different social groups in the Revolt of 1857.

Discuss the regional variations in the intensity and spread of the Revolt of 1857.

Examine the role of Indian leaders in mobilizing masses during the Revolt of 1857.

Critically evaluate the British response to the Revolt of 1857 and the military strategies used to suppress it.

What were the consequences of the Revolt of 1857 on British administrative policies in India?

Explain how the Revolt of 1857 influenced the future course of India’s freedom struggle.

Compare the Revolt of 1857 with earlier uprisings in India. What made 1857 unique?